(C) 2013 Chris M. A. Stapleton. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

Citation: Stapleton CMA (2013) Bergbambos and Oldeania, new genera of African bamboos (Poaceae, Bambusoideae). PhytoKeys 25: 87–103. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.25.6026

Two new monotypic genera, Bergbambos and Oldeania are described for African temperate bamboo species in the tribe Arundinarieae, after a comparison of their morphological characteristics with those of similar species from Asia. Morphological differences are supported by their isolated geographical distributions. Molecular evidence does not support the inclusion of these species in related Asian genera, recognising them instead as distinct lineages. New combinations Bergbambos tessellata and Oldeania alpina are made.

Thamnocalamus, Yushania, Arundinarieae, new genus, Africa

While Asian temperate bamboos have received critical attention over recent decades (

Tribe Arundinarieae contains woody bamboos with semelauctant synflorescences (lacking a capability for indeterminate growth from buds subtended by the basal spikelet bracts), ebracteate or partially bracteate synflorescence paraclades (reduced sheathing subtending inflorescence branches) and 3 stamens in each floret. They constitute ca. 800 of the ca. 1400 woody bamboos, and are found in Asia, Africa, and the USA, having a montane or subtropical to temperate distribution.

Molecular studies reviewed by

Most of the older 3-stamened species were placed at some time in Arundinaria Michx., which has 529 combinations, but that genus is now widely recognised as containing only 3 species, all from the Southeast USA (

There appears to have been a rapid and relatively recent diversification within bamboos with 3 stamens, including tribe Arundinarieae (

In the absence of reliable molecular analyses, for the purpose of descriptive treatments of bamboo species (

Rapid recent diversification seems to have spawned a host of small groups, often distinguished by relatively minor characters. Combining them together into a few large genera has not been possible without establishing excessively variable genera that are difficult to define and demonstrably polyphyletic. On the other hand recognising only half of the genera described would still lead to a generic concept that is unusually narrow in the grasses. The latter procedure has been followed (

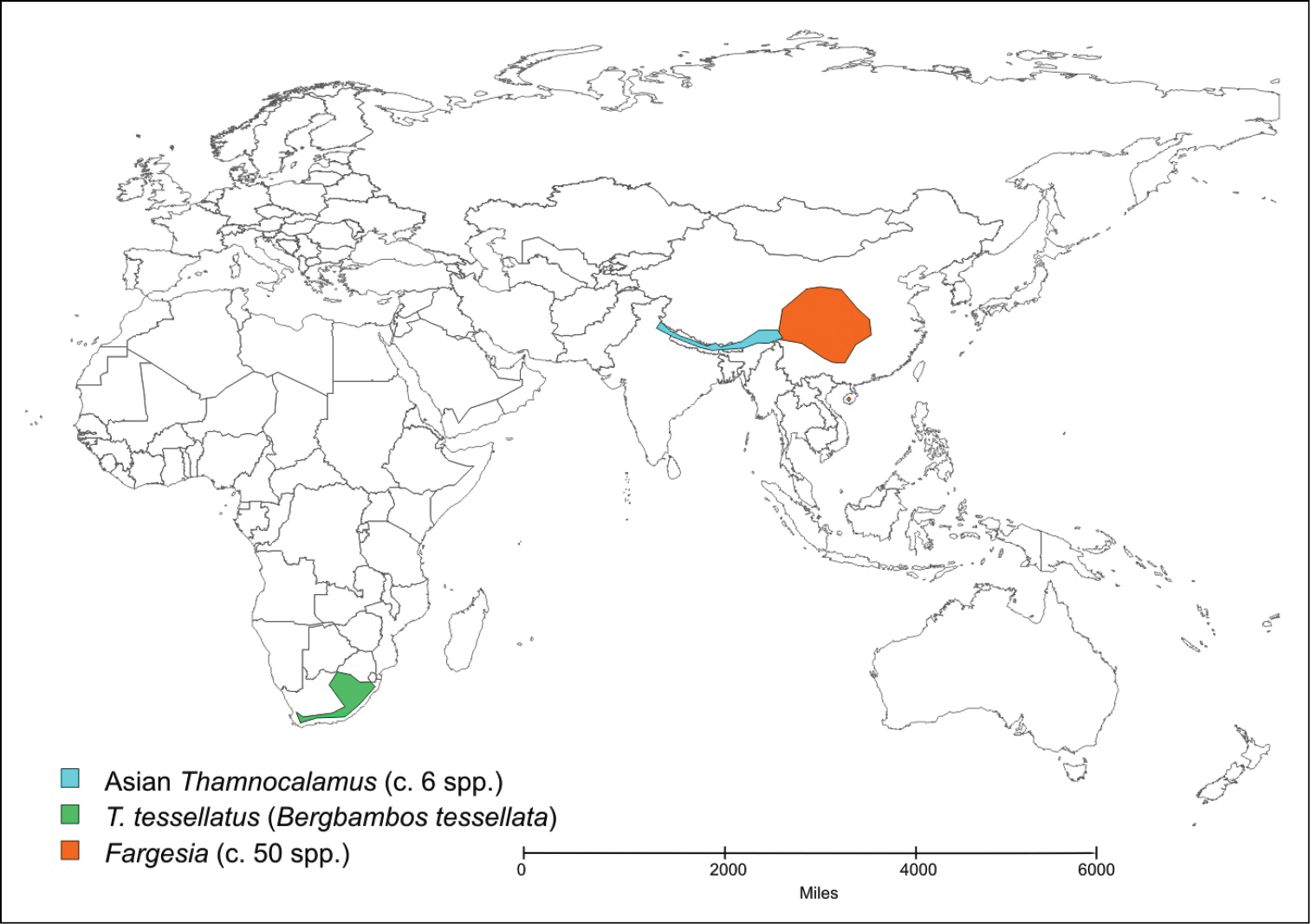

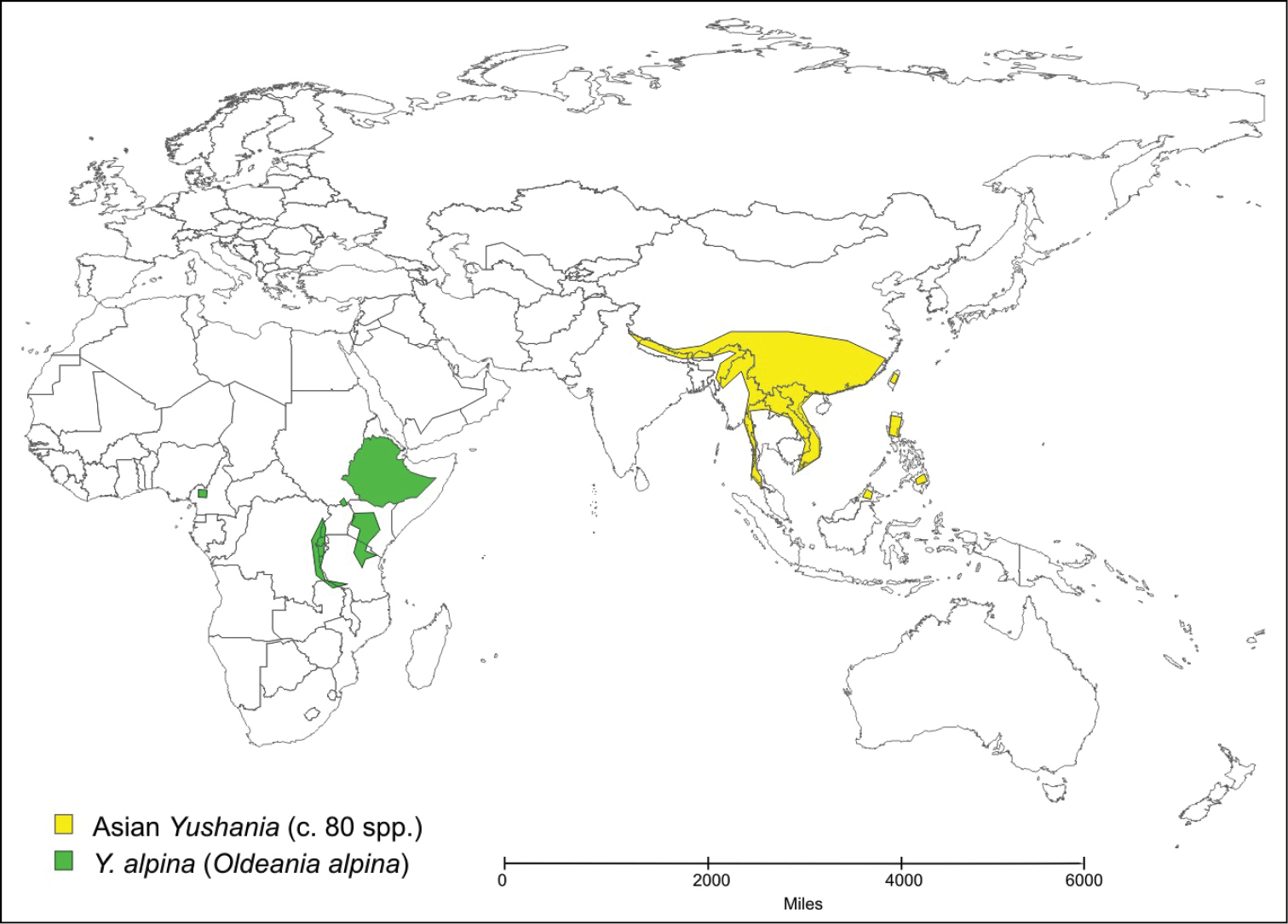

Only two species of temperate bamboo have been described from the African mainland. Thamnocalamus tessellatus (Nees) Soderstrom & R.P. Ellis is from mountains in southern Africa, while Yushania alpina (K. Schum.) W.C. Lin is from mountains in several countries across tropical Africa. Yushania alpina was described initially in Arundinaria, and Thamnocalamus tessellatus was soon transferred into that genus from Nastus Juss. They were more recently moved into the morphologically closer Asian genera, Thamnocalamus Munroand Yushania Keng f., the geographically closest representatives of which are found in the Western Himalayas, Map 1 and Map 2.

Distribution of Thamnocalamus tessellatus, Thamnocalamus in Asia, and Fargesia.

Distribution of Yushania alpina and Asian Yushania species.

Three further, less well known species, Thamnocalamus ibityensis (A. Camus) Ohrnb., Yushania madagascariensis (A. Camus) Ohrnb. and Yushania humbertii (A. Camus) Ohrnb. (including Yushania ambositrensis (A. Camus) Ohrnb.) were described from Madagascar. Thamnocalamus ibityensis has been considered conspecific with Thamnocalamus tessellatus (Chao & Renvoize, 1989), but it would appear to have substantially different branch sheathing. The two Yushania species would appear to share characteristics with Yushania alpina, but their culms, branching and culm sheaths are not known. Yushania ambositrensis resolved in a clade with Yushania alpina (Triplett, 2008), but it is not clear how closely related they really are to Yushania alpina, or to each other, and which species names should be recognised. Further field work on temperate species of Madagascar is required, as existing collections are incomplete, although any such species may have already become extinct.

Systematics within the grass family has traditionally given greater weight to floral than to vegetative characters. This has often led to polyphyletic genera in the bamboos, the superficiality of their similarities and their separate origins only being revealed by in-depth morphological investigations and/or molecular studies. In order to allow deeper, more objective morphological comparisons and to allow inclusion of consistent and accurate vegetative as well as floral characters in descriptions, the morphology of woody bamboos has been reviewed in depth (

The characters and character states considered important at the generic level for distinguishing the two African species from similar Asian genera are given in Table 1.

Principal morphological characters of Bergbambos, Oldeania, and Asian members of 5 similar genera.

| Bergbambos (Thamnocalamus tessellatus) |

Thamnocalamus | Fargesia | Oldeania (Yushania alpina) |

Yushania | Borinda | Chimonocalamus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| synflorescence | raceme, not unilateral | raceme to panicle, not unilateral | raceme, unilateral | panicle, not unilateral | panicle, not unilateral | panicle, not unilateral | panicle, not unilateral |

| paraclades | largely ebracteate | substantially bracteate | variably bracteate | largely ebracteate | largely ebracteate | largely ebracteate | largely ebracteate |

| pedicel | scabrous | glabrous | glabrous | glabrous | glabrous | glabrous | glabrous |

| fertile florets | 1 | 2–several | 2–several | 2–several | 2–several | 2–several | 2–several |

| glume bud remnants | absent | variable | present | absent | variable | variable | absent |

| rhizomes | short-necked | short-necked | short-necked | long-necked | long-necked | short-necked | short-necked |

| clump form | unicaespitose | unicaespitose | unicaespitose | culms solitary | pluricaespitose | unicaespitose | unicaespitose |

| nodes | without roots | without roots | without roots | with short roots | without roots | without roots | with root thorns |

| supranodal ridge | obscure | obscure | obscure | well developed | obscure | obscure | well developed |

| culm internodes | terete | terete | terete | sulcate | terete | terete | terete |

| branch sheathing | reduced | complete | reduced | reduced | reduced | reduced | complete |

| branch orientation | erect | erect | erect | spreading | erect to spreading | erect | spreading |

| mid-culm branches | 5–7 | 3–8 | 5–7 | 3–7 | 5–11 | 5–7 | 3 |

| culm sheath blades | erect or reflexed | usually erect | erect or reflexed | usually reflexed | erect or reflexed | erect or reflexed | usually reflexed |

Previous generic placements of Thamnocalamus tessellatus were based upon an incomplete knowledge of its morphology. Nastus tessellatus Nees was described before its flowers were known, and transferred into Arundinaria (

It was transferred into Thamnocalamus largely on the basis of leaf anatomical characters by

The synflorescence of Thamnocalamus tessellatus has been well illustrated in Hooker’s Icones Plantarum (

Raceme of Thamnocalamus tessellatus (A), compared to: B Fargesia nitida, lateral view with enclosing sheaths; C Fargesia nitida with enclosing sheaths removed D Fargesia nitida, dorsal view, sheaths removed. A from

In addition, in Thamnocalamus tessellatus the pedicels are scabrous, the glumes of each spikelet are basally tight and contain no vestigial bud remnants, and the racemes are usually largely ebracteate. The usually single fertile florets also distinguish Thamnocalamus tessellatus from other Thamnocalamus and Fargesia species, but this character should be treated with caution as it can be a specific as well as a generic character.

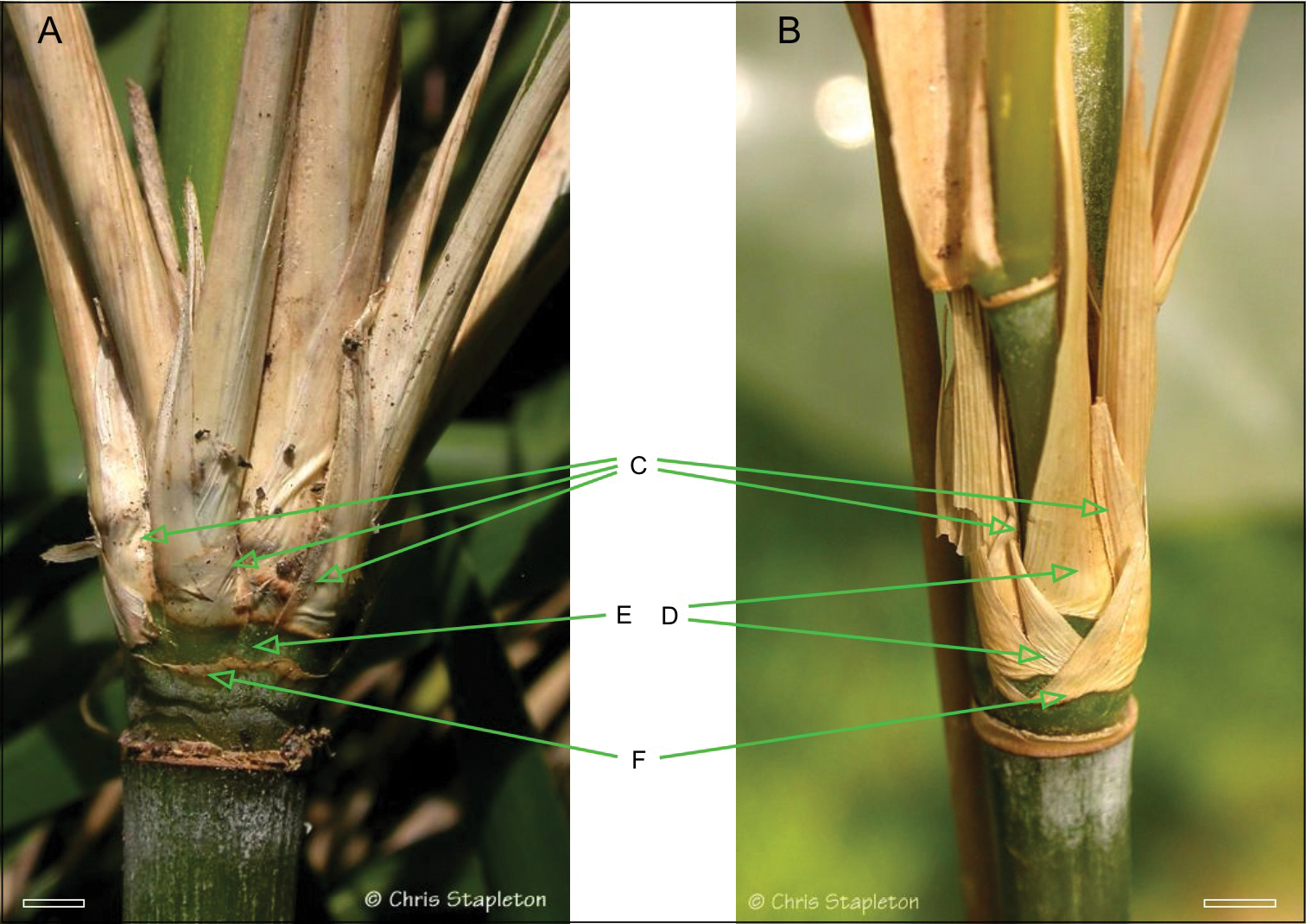

Thamnocalamus tessellatus also hasvegetative characteristics that distinguish it, notably from Asian members of Thamnocalamus, (see Table 1). A close inspection of the branching reveals not the pattern seen in species such as Thamnocalamus crassinodus (T.P. Yi) Demoly, but instead the substantial reduction in sheathing seen in Fargesia, Yushania, and Borinda Stapleton, Figure 2.

Comparison of branch complement sheathing from mid-culm nodes of Thamnocalamus tessellatus (A) and Thamnocalamus crassinodus (B) C Lateral branch prophylls D Sheaths obscuring prophyll bases in Thamnocalamus crassinodus E Equivalent sheaths completely absent in Thamnocalamus tessellatus, prophylls visible F Branch bud prophyll, removed in A, still present in B. Scale bars 1 cm. From http://www.bamboo-identification.co.uk

The branches of Thamnocalamus tessellatus are subequal, arranged side by side through strong compression of the basal internodes of the central branch, accompanied by loss of some of the sheaths at the nodes, Fig. 2A, cf Thamnocalamus crassinodus, Fig. 2B. This allows lateral branch prophylls to be seen side by side without any intervening sheaths. These patterns were contrasted by

In addition to the synflorescence and branching, Thamnocalamus tessellatus also differs in minor details that are harder to quantify, including the more varied orientation of the foliage leaves, and the delicate appearance of its oral setae and their more varied orientation, Figure 3.

Thamnocalamus tessellatus. A Random orientation of leaf blade; B and C Irregular orientation of delicate oral setae. Scale bars A 10 cm, B and C 2 mm. From http://www.bamboo-identification.co.uk/html/tessellatus.html

Thus in terms of vegetative macro-morphological characteristics important at the generic level, Thamnocalamus tessellatus is closer to Fargesia than to Thamnocalamus, but can be distinguished from both. In general appearance it resembles a coastal species of Pleioblastus Nakai from Japan, with rather loose clumps, erect culms with short branches bearing coarse, irregularly arranged foliage with persistent sheaths. This contrasts with the delicate foliage leaves, all oriented towards the light on pendulous branches seen in Himalayan speciesof Thamnocalamus and in Fargesia. This is likely to be associated with the more open ecological habitat in which Thamnocalamus tessellatus is found, rather than the darker forest understorey habitats of Asian Thamnocalamus and Fargesia species.

The synflorescence of Yushania alpina is practically indistinguishable from those of several Asian and American bamboos, including species of Arundinaria, Sarocalamus, and Yushania—an open panicle with nearly complete reduction in sheathing at points of branching so that it is essentially ebracteate. However, the sheaths are often reduced to small tough bracts, as well as the more delicate sheath remnants or tufts of hairs seen in similar genera. In addition the lateral spikelets are more often sessile or subsessile, without a long pedicel. However, these characters are relatively minor and quite variable.

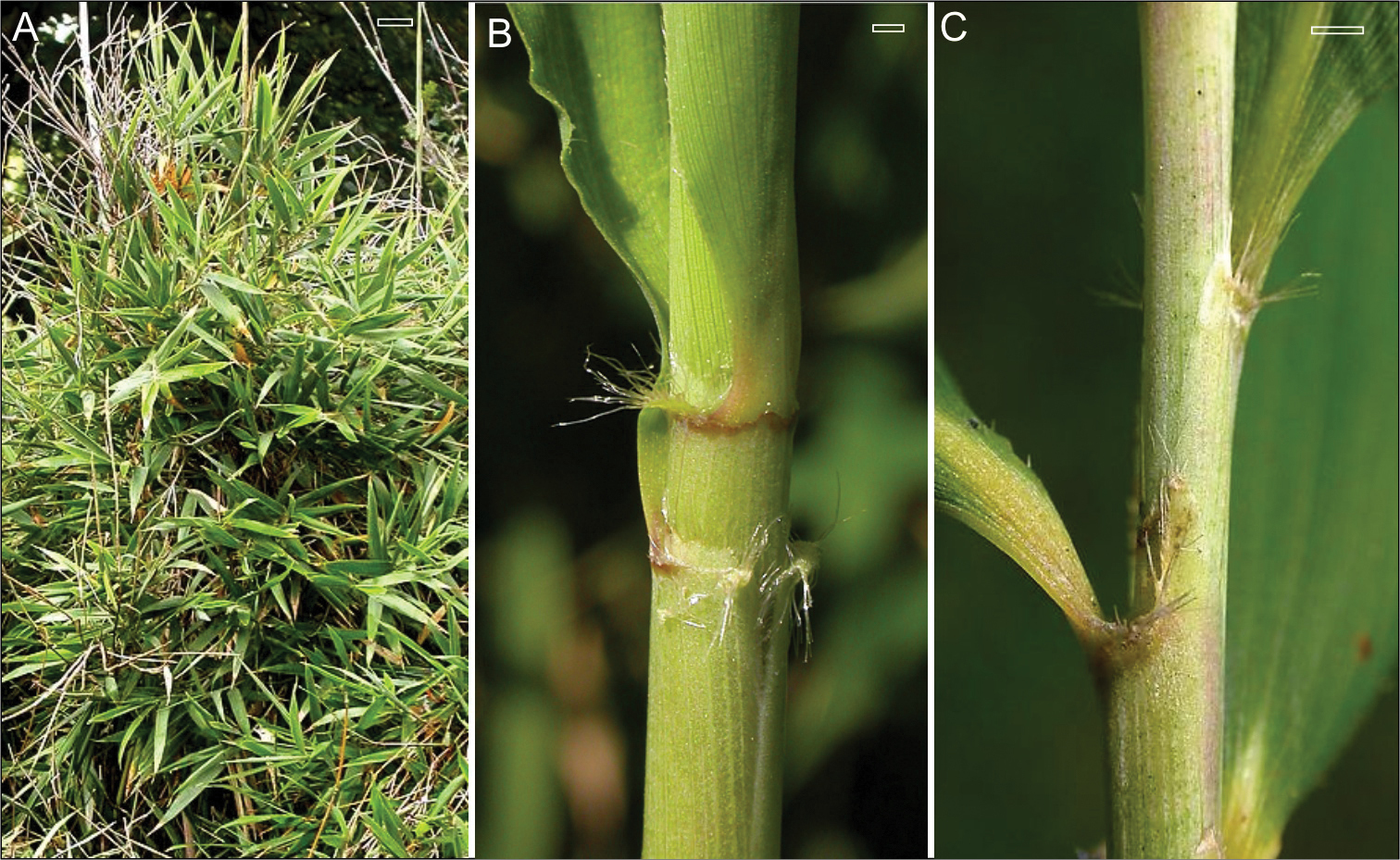

Yushania alpina is more distinct vegetatively. Reaching heights of up to 20m in its natural habitat, the tall, very erect culms are potentially much larger than those of any Asian species of Yushania, which only reach a maximum height of about 7m. Culm nodes and branching also differ substantially from those of Asian species of Yushania, Figure 4.

Yushania alpina. A culm sheath B leaf sheaths, culm node with ring of thorn-like aerial roots and distinct supra-nodal ridge, sulcate internode, and dominant central branch. Scale bars top right, 2 cm.

Branches vary in size more than those of Asian Yushania species. The central branch is strongly dominant, and the first two lateral branches are also strong. The orientation of the branches is less erect than those of most species of Yushania, becoming nearly horizontal. Above the branches the internode is distinctly sulcate, much more prominently than is seen in Asian Yushania species, as a result of the development of strong branches. Moreover there is often a dense ring of short, partially developed aerial roots at nodes in the lower part of the culm, often extending into the mid-culm region as well. This character is only known in species of Chimonocalamus Hsueh & T.P. Yi, and the leptomorph-rhizomed Chimonobambusa Makino among the Asian temperate bamboos. The roots are not as sharp and thorn-like as those seen in Chimonocalamus and Chimonobambusa, but they can be very distinct and prominent. Nodes have a distinct infranode between the culm sheath attachment and the supranodal ridge, which is well developed, Figure 5.

Yushania alpina A tall culms arising separately with prominent supra-nodal ridges (arrowed), Rwenzori, Uganda B culm node with ring of thorn-like aerial roots (arrowed), Mt. Kenya.Scale bars A 25 cm, B 5 cm. Photos courtesy of: (A) Peter Gill, (B) Harry Jans, www.jansalpines.com

In its natural habitat, the open stands have a widely spaced appearance closer to that of a species of Phyllostachys Siebold & Zucc., rather than the denser thickets of Asian Yushania species, because the rhizomes have consistently long necks, giving solitary culms rather than the denser clusters of pluricaespitose culms seen in Asian species of Yushania.

Branch structure and sheathing is difficult to distinguish from that of Yushania or Fargesia. Although the prophyll is usually 2-keeled, there is replication side by side of lateral branch initials without intervening sheaths. In this way it differs fundamentally from Chimonocalamus, which has only 3 branches and full sheathing.

The morphological differences between Thamnocalamus tessellatus, Yushania alpina and other representatives of these and similar Asian genera suggest that although the two African bamboos share several characters and presumably common ancestors with Asian bamboos, they are not as closely related to their Asian relatives as previously thought.

The morphological distinctions are supported by geographical isolation, (see Maps 1 and 2). Long-distance dispersal of temperate bamboos is highly unlikely because of a lack of any specialized seed dispersal mechanism or dormancy, brief viability of seed, exacting habitat requirements, and extremely infrequent flowering (

Together the morphological distinctions and geographical isolation justify the recognition of two new genera, following the existing relatively narrow generic concepts applied in the northern temperate clade, tribe Arundinarieae.

The new genera are keyed out below along with their 6 morphologically closest relatives in the tribe including the two Asian genera with distinct nodal thorns, as well as the North American type genus of the tribe, Arundinaria, and its Asian analogue, Sarocalamus.

| 1 | Rhizome leptomorph | 2 |

| – | Rhizome pachymorph | 4 |

| 2 | Basal culm nodes with thorns, branches spreading | Chimonobambusa |

| – | Basal culm nodes without thorns, branches erect | 3 |

| 3 | Pedicels glabrous, leaf blades thick, SE USA | Arundinaria |

| – | Pedicels not glabrous, leaf blades thin, Himalayas & W China | Sarocalamus |

| 4 | Branches 3, all sheaths developed, basal nodes with thorns | Chimonocalamus |

| – | Branches 3-15, sheathing reduced, basal culm nodes with or without thorns | 5 |

| 5 | Rhizomes long or variable in length, clumps open or spreading | 6 |

| – | Rhizomes consistently short, culms in single clumps | 7 |

| 6 | Nodes raised, basal culm nodes usually with thorns, Africa | Oldeania |

| – | Nodes not raised, basal culm nodes without thorns, Asia | Yushania |

| 7 | Branch sheathing complete | Thamnocalamus |

| – | Branch sheathing reduced | 8 |

| 8 | Synflorescence branching paniculate | Borinda |

| – | Synflorescence branching racemose | 9 |

| 9 | Racemes unilateral, W China | Fargesia |

| – | Racemes not unilateral, Africa | Bergbambos |

Sufficient data is now available to test whether this classification would gain support from molecular phylogenetic evidence. These two African species were not clearly resolved with Asian representatives of any genera in any molecular studies. For example, in a comparison of ITS sequences (

The molecular data would suggest that their inclusion in Asian genera would render those genera polyphyletic. Because their monotypic status is considered likely they could not be supported as monophyletic groups themselves in a classification based solely on molecular phylogeny. However,

Although woody bamboos are considered to have evolved originally in Gondwanaland rather than Eastern Asia (

Collision of tectonic plates has been suggested as a likely cause of this rapid radiation (

Differing from Arundinaria and Sarocalamus and similar to Thamnocalamus and Fargesia in its short-necked pachymorph rather than leptomorph rhizomes, and its compressed synflorescences. Differing from Borinda and Thamnocalamus in its racemose rather than paniculate synflorescence branching. Differing from Fargesia in the distichous rather than unilateral arrangement of spikelets in the racemes, the spikelets usually having only one fertile floret, and the scabrous pedicels. Differing from Thamnocalamus in the branch complement with reduced sheathing, and from Fargesia in the more varied orientation of the leaf blades.

Bergbambos tessellata (Nees) Stapleton comb. nov. urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:77131104-1 Basionym: Nastus tessellatus Nees, Fl. Afr. Austr. 1: 463. 1841. Arundinaria tessellata (Nees) Munro; Thamnocalamus tessellatus (Nees) Soderstrom & R.P. Ellis. Type: S Africa, Katberg, 4000–5000ft, J.F. Drège s.n. (lectotype, designated in Soderstrom & Ellis 1982, pg. 54: K!, http://apps.kew.org/herbcat/getImage.do?imageBarcode=K000345516

Rhizome pachymorph, short-necked, giving dense clumps. Culms to 7 m tall, diam. to 2 cm, nodding to pendulous, terete, smooth, nodes not raised and unarmed. Mid-culm branch complement initially with 5–7 main branches, erect, sheathing reduced. Culm sheaths persistent, tough. Leaf sheaths several to many, persistent, blades thick with random orientation. Synflorescence semelauctant, racemose, branch sheathing occasionally a soft sheath remnant, usually absent. Racemes not unilateral. Spikelets shortly pedicellate with 1(–2) fertile florets, pedicel scabrous. Empty glumes 2, no bud remnants. Lemma and palea similar in length. Stamens 3, filaments free. Stigmas 3. Lodicules 3.

Name Bergbambos from the Afrikaans name (Bergbamboes) in South Africa.

This genus would appear to be monotypic, confined to the mountains of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland.

Differing from Arundinaria and Sarocalamus and similar to Yushania in its long-necked pachymorph rather than leptomorph rhizomes, though similar to all in its open panicles. Differing from Yushania in its sulcate culm internodes, fewer, more horizontal branches, culm nodes with well developed supra-nodal ridge and often thorn-like aerial roots. Similar to Chimonocalamus in its panicles and thorn-like roots at culm nodes, but differing in its multiple branches with reduced sheathing and sulcate culm internodes.

Oldeania alpina (K. Schum.) Stapleton comb. nov. urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:77131105-1 Basionym Arundinaria alpina K. Schum. in Engler, Pflanzenwelt Ost-Afrikas 5: 117. 1895. Sinarundinaria alpina (K. Schum.) C.S. Chao & Renvoize; Yushania alpina (K. Schum.) W.C. Lin. Type: Kenya, Kikiju, G.A. Fischer 672 (holotype: B n.v., destroyed).

Rhizome pachymorph, long-necked, giving open stands and solitary culms. Culms to 15(–20) m tall, diam. to 6(–10) cm, erect to nodding, terete with shallow sulcus above branches, smooth, nodes with prominent supranodal ridge, in lower to mid culm a nodal ring of dense, short, hard, and thorn-like aerial roots often well developed. Mid-culm branch complement initially with 3–5 main branches, spreading, sheathing reduced. Culm sheaths deciduous, tough. Leaf sheaths several to very many, blades thick. Synflorescence semelauctant, paniculate, branch sheathing reduced to hard bracts, soft sheath remnants or hairs. Spikelets pedicellate with several fertile florets, pedicel scabrous. Empty glumes 2, bud remnants present or absent, fertile glumes 4–8. Lemma and palea similar in length. Stamens 3, filaments free. Stigmas 2. Lodicules 3.

Name Oldeania from the Maasai common name (Oldeani) in Tanzania.

Currently only the type species can be reliably placed in the genus, which thus has a distribution across tropical Africa from Cameroon in the west to E Africa, where it occurs from Ethiopia south to Tanzania. There is a possibility that species from Madagascar will be placed in this genus when they are better known, but they may be conspecific or even introduced. It provides important montane wildlife habitats and food, notably for the critically endangered Mountain Gorilla, Gorilla beringei beringei.

The holotype, G.A. Fischer 672, was destroyed by fire during the 1939–1945 World War. No trace of the type collection or any duplicate has been found in surviving components of the Berlin collections, nor in other herbaria, including the Hamburg collections taken to Russia and recently repatriated (Poppendieck pers. comm.). The likelihood of substantial infraspecific variation, the possibility of further species, and the lack of other collections from the type locality together make it inadvisable to select a neotype or epitype until new collections have been made.

The American Bamboo Society is thanked for providing open access publication fees for this paper. Dr Hans-Helmut Poppendieck, Curator of Phanerogams at Herbarium Hamburgense is thanked for information relating to the missing type of Arundinaria alpina. Dr Ximena Londoño kindly looked for ms names while at the Smithsonian Institute, and Dr John Grimshaw provided information on African local names. Dr Sylvia Phillips arranged for collection of DNA samples in Ethiopia. Dr Eric Boa, Dr Peter Gill, and Harry Jans provided photos from Ethiopia and Uganda. Dr Martin Cheek at RBG Kew encouraged me to persevere with African bamboos. Journal editor Dr Leonardo Versieux and the anonymous reviewers are thanked for their valuable comments.