(C) 2012 Mario Vallejo-Marín. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

Polyploidization plays an important role in species formation as chromosome doubling results in strong reproductive isolation between derivative and parental taxa. In this note I describe a new species, Mimulus peregrinus (Phrymaceae), which represents the first recorded instance of a new British polyploid species of Mimulus (2n = 6x = 92) that has arisen since the introduction of this genus into the United Kingdom in the 1800’s. Mimulus peregrinus presents floral and vegetative characteristics intermediate between Mimulus guttatus and Mimulus luteus, but can be distinguished from all naturalized British Mimulus species and hybrids based on a combination of reproductive and vegetative traits. Mimulus peregrinus displays high pollen and seed fertility as well as traits usually associated with genome doubling such as increased pollen and stomata size. The intermediate characteristics of Mimulus peregrinus between Mimulus guttatus (2n = 2x = 28)and Mimulus luteus (2n = 4x = 60-62), and its close affinity with the highly sterile, triploid (2n = 3x = 44-45) hybrid taxon Mimulus × robertsii (Mimulus guttatus × Mimulus luteus), suggests that Mimulus peregrinus mayconstitute an example of recent allopolyploid speciation.

Allopolyploidy, Erythranthe, hybrid evolution, introduced species, Mimulus guttatus, Mimulus luteus, rapid evolution, speciation

The genus Mimulus (Phrymaceae) comprises more than 120 species, the majority (75%) of which occur in western North America, and the remaining having a world-wide distribution including Eastern North America, South America, Australia, the Himalayas, Japan and Madagascar (

One of the most conspicuous hybridization complexes in the UK involves closely related taxa, of isolated geographic origin: the North American Mimulus guttatus DC. (2n = 28, 30, 56, with most North American and British plants 2n = 2x = 28,

Despite being widely distributed and having persisted in the UK for 140 years, the evolutionary fate of Mimulus guttatus × Mimulus luteus/Mimulus cupreus triploid hybrids has been thwarted by their high pollen- and seed-sterility (

Polyploidization plays a particularly important role in species formation, as chromosome doubling results in immediate and strong reproductive isolation between the derivative and parental species (

In this note, I describe a new, fertile, polyploid (2n = 6x = 92) species of Mimulus (Phrymaceae), Mimulus peregrinus, which has currently been found in a single locality in the Lowther Hills, Scotland. A comparison of vegetative and reproductive morphology, DNA content, and chromosome number of this new polyploid species against other British Mimulus, strongly suggests a hybrid origin for Mimulus peregrinus and a close affinity with the sterile triploid hybrid Mimulus × robertsii. I speculate that Mimulus peregrinus may represent the hexaploid derivative of a hybrid between Mimulus guttatus and Mimulus luteus, although a careful examination of additional populations of both parental and hybrid taxa is required to elucidate the genetic origin, extent and distribution of this new polyploid species. If an allopolyploid origin is demonstrated, Mimulus peregrinus has the potential to serve as a study system to understand the evolutionary processes associated with the origin of species through hybridization and polyploidization following the breakdown of geographic barriers caused by human-assisted dispersal.

MethodsField surveys in August 2011 uncovered the existence of fertile individuals in a large population of Mimulus × robertsii in South Lanarkshire, Scotland. To further investigate these unusual plants, open-pollinated seeds were collected on 27 August 2011 from multiple seed-bearing fruits in a single patch at Shortcleuch Waters, near Leadhills, South Lanarkshire, Scotland (NS 9029 1578; 55.4237°N, 3.7349°W). Field-collected seeds—accession number 11-LED-seed—were germinated and grown in a controlled environment cabinet (Microclima 1750E; Snijders Scientific, Tilburg, the Netherlands) at the University of Stirling under 16 light-hours at 24°C and 8 dark-hours at 16°C, and 70% constant humidity. Individual plants were grown in 0.37 l round pots, filled with general purpose peat-sand compost (Sinclair, Lincoln, Lincolnshire, UK), and kept on plastic trays with abundant water. Plants were sporadically treated with SB Plant Invigorator (Fargro Ltd, Littlehampton, West Sussex, UK) to control for fungal infections. Seven plants were brought to flowering (F1 generation; 11-LED-seed-1 to 11-LED-seed-7), and each individual plant was used to generate F2 offspring via manual self-fertilization of emasculated flowers kept inside the pollinator-free growth cabinet. A representative individual of this F2 generation (11-LED-seed-2-14) was chosen as the holotype for the type description presented here (deposited at the Herbarium of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh; E).

Pollen measurements were conducted using fresh pollen fixed in 1 ml of 70% ethanol and dyed with 50 μl of lactophenol-aniline blue (Kearns and Inouye 1993). Darkly stained grains were considered viable (

Stomata size was measured in casts obtained from the adaxiall side of healthy leaves. A negative cast was first obtained with polysiloxane precision impression material (Xantoprene VL Plus, Heraeus Kulzer Gmbh, Hanau, Germany), and a positive cast was then generated with quick-drying nail polish. Measurements of stomata length and width were done using a light microscope at 400×.

Chromosome counts were conducted by John Bailey (University of Leicester) in mitotic cells from root tips of two F2 individuals (11-LED-seed-3-21 and 11-LED-seed-5-8). Genome size was measured using DAPI-stained nuclei analysed in a CyFlow ML flowcytometer (Partec GmbH, Münster, Germany) in a commercial facility (Plant Cytometry Services, Schijndel, The Netherlands) in six F1 individuals (11-LED-seed-1 to 11-LED-seed-4, 11-LED-seed-6, 11-LED-seed-7). Vinca major was used as internal standard (2n = 92, 2C = 3.80 pg; Obermayer and Greihulber 2006). Because DAPI preferentially binds to AT-rich regions, the flow cytometry results presented here must not be treated as absolute measurements of DNA content.

Data resourcesThe data underpinning the analysis reported in this paper are deposited at GBIF, the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, http://ipt.pensoft.net/ipt/resource.do?r=mimulus_peregrinus

Taxonomic treatmenturn:lsid:ipni.org:names:77120497-1

http://species-id.net/wiki/Mimulus_peregrinus

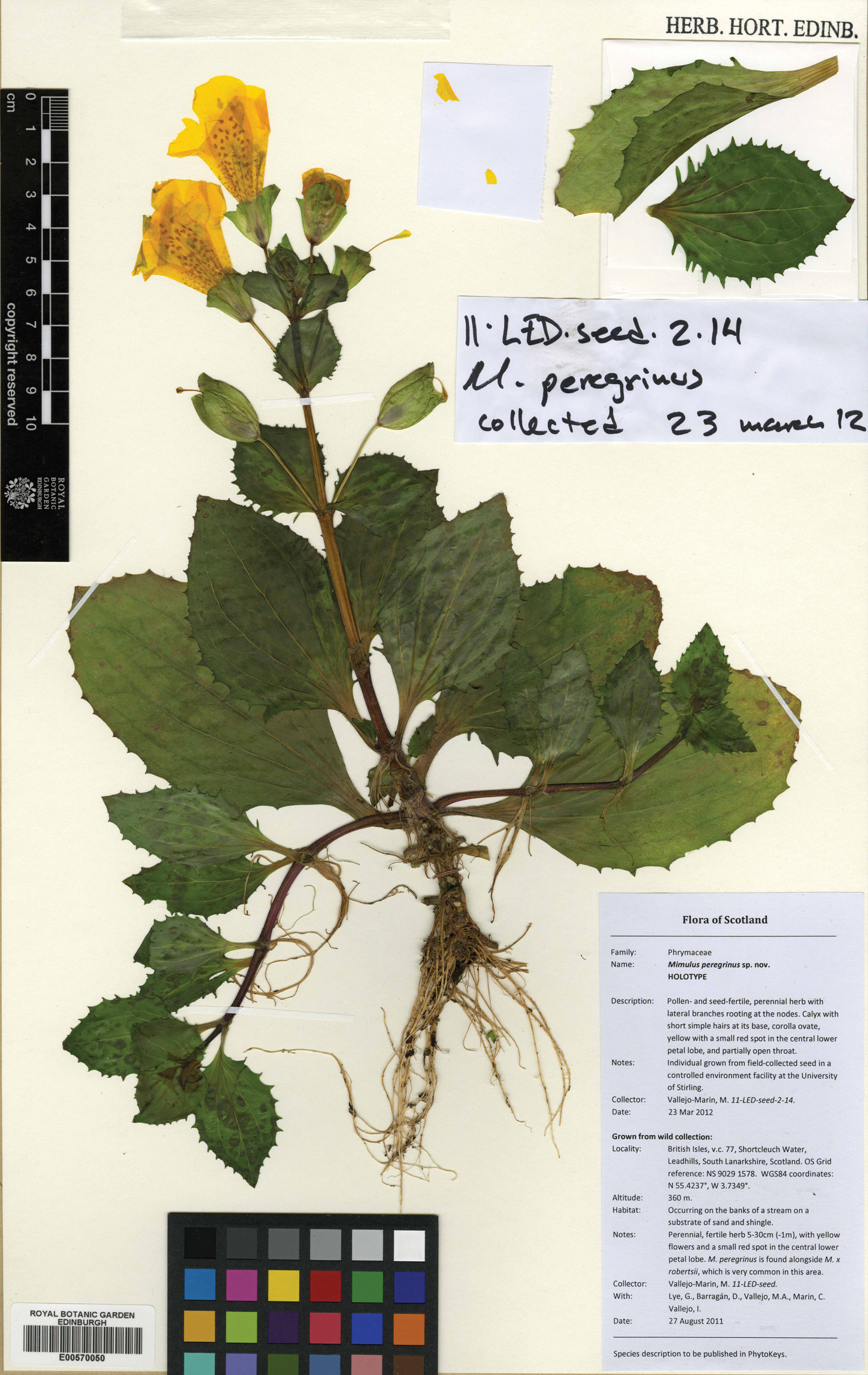

Figure 1United Kingdom. Scotland: Grown from seed collected in South Lanarkshire near Leadhills, on the banks of Shortcleuch Water. Vice county 77, Ordinance Survey grid reference: NS 9029 1578. WGS84 coordinates: 55.4237°N, 3.7349°W; altitude: 360 m. 27 Aug 2011. M.Vallejo-Marín 11-LED-seed; vouchered as M.Vallejo-Marín 11-LED-seed-2-14 (holotype: E; isotypes: BM, K).

Species nova Mimulus × robertsii Silverside similis. Herba perennis, pollen et semen fertile, corollae, flavae, lobo centrali cum macula parva rubro. Folia ovata ad oblonga, dentata, regulariter ad irregulariter triangulo-dentata. Calyx interne cum capillis simplicibus instructis.

Perennial herb 5-30 cm (–1 m) high, freely rooting at the nodes. Stem erect or prostrate, glabrous below and glandular pubescent above. Leaves variable, mostly ovate-oblong 3–14 × 1.5–4 cm, with regular to irregularly dentate margins; basal leaves oval to spatulate, with petioles up to three-quarters as long as the blades; upper leaves ovate with much shorter petioles or sessile. Inflorescence racemose, many-flowered; pedicels 2.5–5 cm long, normally equalling or slightly longer than the corolla, but shorter in later flowers. Calyx 1.5–2.5 cm long, with 5 triangular teeth, the upper tooth distinctly longer; pubescent outside covered with glandular hairs throughout, and with short, simple hairs in the base of the calyx extending along the ridges; calyx becoming inflated in fruit, with the lower two calyx-teeth curving upwards and enclosing the fruit. Corolla ovate in frontal view, 4–5 cm wide, 3–5 cm tall, and 4–5 cm long (deep); the lobes almost truncate, particularly the two lateral ones; yellow, with a single faint-red, vertically-elongated 2 × 5 mm spot located approximately half-way on the central lower lobe; throat hairy, spotted with red, more or less open; lobes subequal, the central lower lobe slightly longer (Fig. 2). Style glabrous, ending in a bi-lobed, thigmotropic stigma. Fruit a broadly oblong capsule; seeds striate, very small (<0.02 mg; ~0.1 mm2). Anthers yielding abundant quantities of viable pollen (percent of viable pollen: 86.39 ± 4.01%, range: 73.24 – 96.40%, N = 6 individuals); pollen diameter from 53.43 ± 1.22 μm (mean ± SE; N =5 individuals, 100 pollen grains per individual; Hoyer’s medium) to 48.78 ± 0.97μm (mean ± SE; N =6 individuals, 100 pollen grains per individual; 70% ethanol) depending on mounting medium. Sets abundant seed following artificial self-pollination. Germination rates of self-fertilized seed 80% ± 4.2% (N =6 families, 50 seeds per family). Stomata length 35.44 μm ± 0.99 (N = 7 individuals, 20 stomata per individual). Chromosome number 2n = 92 (J. Bailey).

Holotype of Mimulus peregrinus Vallejo-Marin [11-LED-seed-2-14; barcode E00570050].

Currently known only from the banks of Shortcleuch Waters, Leadhills, South Lanarkshire, Scotland, UK (v.c. 77).

Occurring on the banks of a stream on a substrate of sand and shingle. Mimulus peregrinus is found alongside Mimulus × robertsii, whichis locally common. Flowering of Mimulus in this region starts in early June. Seeds of Mimulus peregrinus were collected in August.

The name is taken from the Latin peregrinus – foreigner, traveller.

Currently known only from a single collection outside of a protected area, Mimulus peregrinus is provisionally assessed as Critically Endangered (CR D; population size estimated to number less than 50 mature individuals) (

United Kingdom. Scotland: Grown from seed collected at South Lanarkshire near Leadhills, on the banks of Shortcleuch Water. 55.4237°N, 3.7349°W; altitude: 360m. 27 Aug 2011. M.Vallejo-Marín, seed voucher: 11-LED-seed. All Mimulus peregrinus specimens examined here were derived from open-pollinated seed collected at the type locality and grown in a controlled environment. Some of these first generation seed-grown individuals (11-LED-seed-1 to 11-LED-seed-7) were then used produce a second generation via self-fertilization (e.g. 11-LED-seed-2-14).

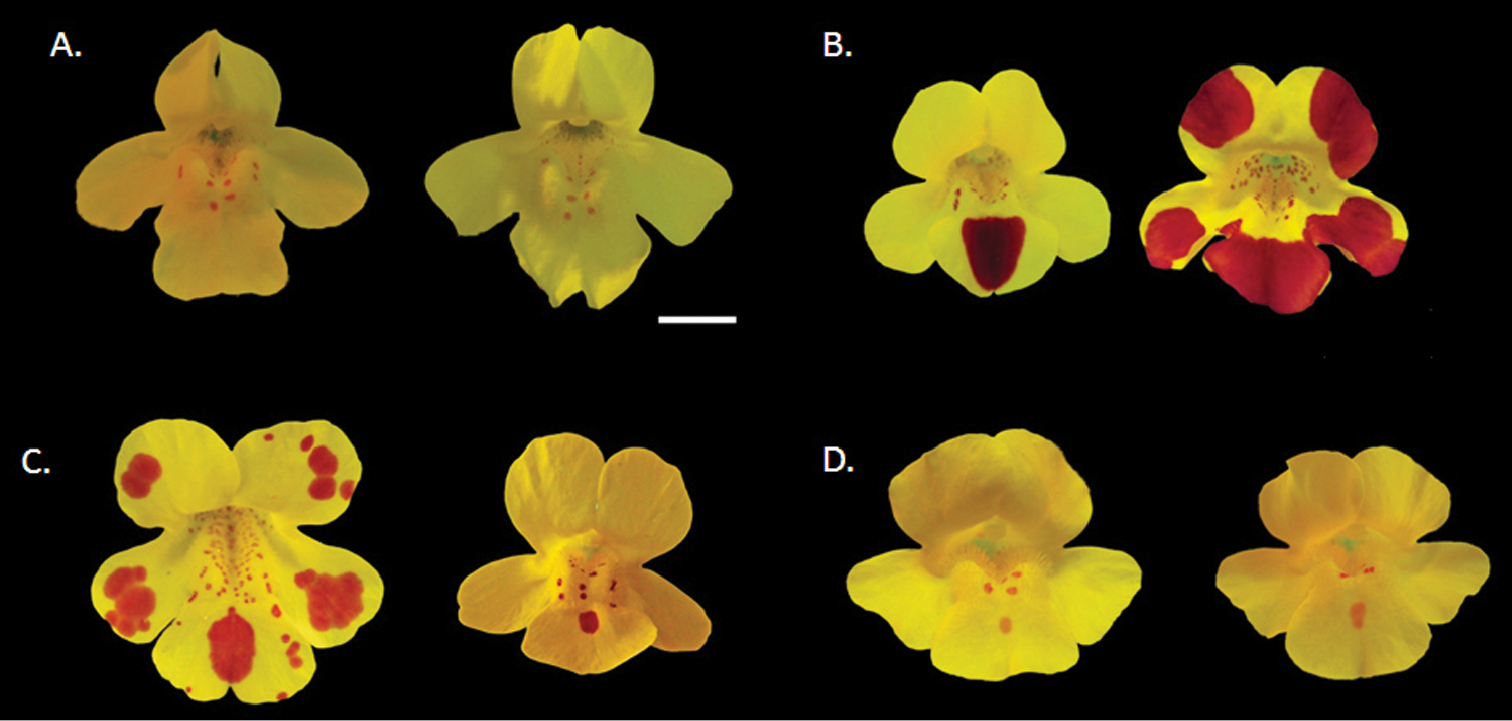

Mimulus peregrinus can be distinguished from closely related Mimulus species and their hybrids in the UK based on a number of morphological and functional characters (Table 1, Fig 2). Its chromosome number, DNA content, larger stomata and pollen grain size, clearly indicate that Mimulus peregrinus is a polyploid species. Although the parentage of this new polyploid has not been firmly established yet, its close affinity with Mimulus × robertsii suggest that Mimulus peregrinus has been derived from hybridization between Mimulus guttatus and Mimulus luteus and thus it might have arisen through a recent (<140 years) allopolyploidization event. Below I contrast Mimulus peregrinus with related Mimulus taxa in the UK, and end with a brief discussion on its putative origin.

List of main diagnostic characters differentiating Mimulus peregrinus from other closely related taxa of Mimulus found in the UK. In the cases of the very variable species Mimulus guttatus and Mimulus luteus, diagnostic characters are taken from those of British populations. For example, although Mimulus luteus is polymorphic for corolla-lobe red markings in Chile, the un-marked variety is not naturalized here (

| Character | Mimulus peregrinus | Mimulus guttatus | Mimulus luteus | Mimulus × smithii | Mimulus × robertsii |

| Corolla lobes with reddish spots or blotches | Yes (one small spot in lower, central lobe) | No | Yes (a single blotch in central lower petal) | Yes (present in 1-5 lobes) | Yes (variable) |

| Throat of corolla | ± open | ± closed | ± open | ± open | ± open |

| Small, simple (non-glandular) hairs on inflorescence and calyx keels | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Seed fertile | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Seed size (area in mm2) | 0.167 ± 0.012 (6) | 0.126 ± 0.008 (12) | 0.103 (1) | 0.112 ± 0.006 (8) | --- |

| Seed germination | 0.80 ± 0.04 (6) | 0.85 ± 0.02 (11) | NA | 0.47 ± 0.06 (8) | -- |

| Pollen fertile (proportion viable) | Yes 0.864 ± 0.040 (6) | Yes 0.865 ± 0.053 (6) | Yes (NA) | Yes 0.963 ± 0.006 (2) | No 0.001 ± 0.001 (9) |

| Mean pollen diameter (μm) 1 | 48.77 ± 0.97 (6) | 36.72 ± 0.38 (24) | 44.08 ± 3.112 (2) | 45.09 ± 0.39 (25) | 37.02 ± 1.703 (9) |

| Stomata size (length, μm)4 | 35.44 ± 0.99 (7) | 28.25 ± 0.42 (1) | NA | 29.67 ± 0.55 (1) | 26.83 ± 0.77 (1) |

| Chromosomes (ploidy) | 2n = 92 (6x) | 2n = 28 (2x) | 2n = 59, 60, 61, 62 (4x) | 2n = 60, 61, 62 (4x) | 2n = 44, 45 (3x); 2n = 54 |

Flowers of Mimulus peregrinus and closely related taxa. A Mimulus guttatus B Mimulus × smithii (Mimulus luteus luteus × Mimulus luteus variegatus) C Mimulus × robertsii (Mimulus guttatus × Mimulus luteus), and D Mimulus peregrinus. Each taxon is represented by flowers from two individuals from a single locality to illustrate within-population variability: Mimulus guttatus = Dunblane, Perthshire; Mimulus × smithii = Coldstream, Scottish Borders; Mimulus × robertsii = Nenthall, Cumbria; Mimulus peregrinus = Leadhills, South Lanarkshire. Scale bar = 1cm.

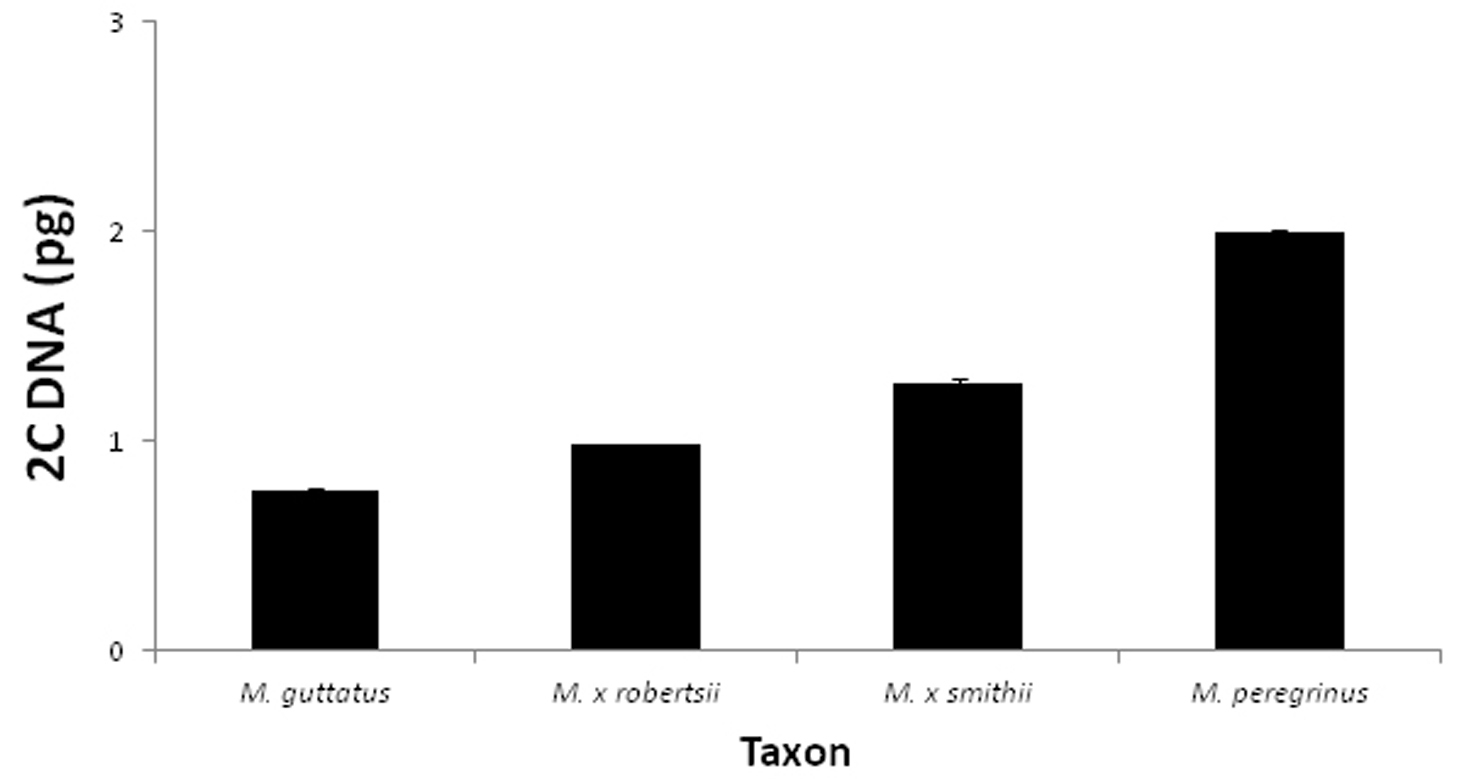

1. Mimulus guttatus DC. (Section Simiolus Green) (yellow monkeyflower). Mimulus peregrinus has a more open corolla throat, in contrast to the nearly closed corolla throat of Mimulus guttatus. The 2–5 mm red spot in the central lower lip of Mimulus peregrinus, is absent in most British populations of Mimulus guttatus. The margins of the lower leaves of Mimulus peregrinus are more triangular and regular than those of most Mimulus guttatus, although leaf traits are highly variable in the genus. Field and herbarium specimens could potentially be distinguished by the much larger size of the pollen grains in Mimulus peregrinus. Chromosome number and genome content as measured in flow cytometry are also diagnostic characters to distinguish these two species (Table 1, Fig. 3).

Flow-cytometry estimates of 2C DNA content (DAPI-stained) of British Mimulus. Error bars represent standard errors when multiple individuals per taxon were tested. Sample sizes as follows (chromosome numbers for each population are given in parenthesis when available). Mimulus guttatus: N = 4 individuals from Dunblane, Perthshire (2n = 28); and 2 individuals from Muckle Roe, Shetland; Mimulus × robertsii (= Mimulus guttatus × Mimulus luteus): N= 1 individual from Nenthall, Cumbria (2n = 44, 45); Mimulus × smithii (= Mimulus luteus var. luteus × Mimulus luteus var. variegatus): N = 2 individuals from Coldstream, Scottish Borders (2n = 59, 60, 61, 62); Mimulus peregrinus: N = 6 individuals from Leadhills, South Lanarkshire (2n = 92).All chromosome counts kindly provided by J. Bailey.

2. Mimulus luteus L. (Section Simiolus Green) (blood-drop emlets). Mimulus luteus, is a group of polymorphic perennial herbs comprising several interfertile varieties that are distinguished based on the presence, size and colour of markings on the corolla lobes. Taxa in this group include Mimulus luteus var. rivularis Lindl. 1826, with a single large red spot on the middle lower lip; Mimulus luteus var. variegatus (Lodd.) Hook 1834, with pale yellow corollas tinted with pink at the lobe margins; and Mimulus luteus var. youngana Hook 1834 (= Mimulus smithii Lindl 1835, not Paxton), with deep yellow corollas and lobes with large red spots at the margins (

3. Mimulus cupreus Dombrain (Section Simiolus Green) (copper monkeyflower). Mimulus cupreus with orange to yellow corollas, and which is closely related to Mimulus luteus, has been reported in the UK but most likely in error for the hybrid between Mimulus guttatus and Mimulus cupreus (Mimulus × burnetii S. Arn.) (

(3) Mimulus moschatus Douglas ex Lindl. (Section Paradanthus Grant) (musk). Mimulus moschatus is easily distinguished from other British Mimulus including Mimulus peregrinus by its smaller yellow corollas (1–2.5 cm), glandular-hairy pubescence throughout the plant, and chromosome number (2n = 4x = 32 × = 8, 9, 10,

(4) Mimulus × robertsii Silverside (Mimulus guttatus × Mimulus luteus). A highly pollen- and seed-sterile, perennial herb rooting at the nodes, its yellow flowers are marked with orange to red to brown spots of various sizes in the petal lobes (

Mimulus peregrinus resembles Mimulus × robertsii rather closely in habit, size and general vegetative and floral morphology, suggesting a close affinity between these two taxa (Table 1). Mimulus × robertsii and Mimulus peregrinus can be distinguished by their differences in chromosome number, pollen and seed fertility, pollen grain size, and stomata size (Table 1). Mimulus peregrinus presents consistently high levels of pollen fertility (0.86 ± 0.04) and is capable of producing abundant seed set following artificial pollination. In contrast, both natural and artificial specimens of Mimulus × robertsii present very low levels of pollen viability (proportion of viable pollen = 0.05 ± 0.01, for both naturalized (N = 7) and synthetic hybrids (N = 15)), and do not set seed following artificial pollination (

(5) Other hybrids. Mimulus × burnetii S. Arn. (Mimulus guttatus × Mimulus cupreus) is a sterile triploid (2n = 45) with copper-coloured corolla, and often presenting a petaloid calyx (

The intermediate floral and vegetative characteristics of Mimulus peregrinus between Mimulus guttatus and Mimulus luteus, as well as its close morphological similarity to Mimulus × robertsii clearly suggest a hybrid origin for this new taxon associated with a polyploidization event. The alternative, that Mimulus peregrinus is an autopolyploid derivative of a pure Mimulus guttatus or Mimulus luteus seems highly unlikely based on vegetative and floral characteristics of the different taxa (Table 1). Moreover, both chromosome counts and genome size data are inconsistent with the expectations of an early generation autopolyploid of either Mimulus guttatus or Mimulus luteus or a backcross between Mimulus × robertsii and either parent (Fig. 3). The fact that Mimulus peregrinus presents approximately twice the number of chromosomes and has double the amount of DAPI-staining DNA than a common cytotype of Mimulus × robertsii (Fig. 3), immediately suggests that the most parsimonious explanation for the origin of Mimulus peregrinus is through hybridization between Mimulus guttatus and Mimulus luteus linked to a polyploidization event. Given that Mimulus peregrinus was indentified amongst a large population of Mimulus × robertsii, a possible origin of this new taxon is via genome doubling of the triploid hybrid.

The known distribution of Mimulus peregrinus iscurrently restricted to a single locality in Scotland. A preliminary examination of herbarium specimens at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Edinburgh did not uncover any hybrid specimens that were obviously fertile. However, the widespread distribution of Mimulus × robertsii in the UK suggests, along with anecdotal records of fertility in hybrids (

It is well known that polyploidization can act as a mechanism restoring fertility even in highly sterile triploid hybrids (

John Bailey has provided considerable support during the development of this study, and generated all the chromosome counts of the material presented here. I am grateful to the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, particularly Hannah Atkins and Adele Smith for help with the preparation of herbarium specimens. I thank G. Lye, M. Vallejo de Anda, C. Marín, D. Barragán, I. Vallejo and E. Marín for assistance with the location and collection of type material, and J. Weir, J. Scriven, P. Monteith, T. Houslay, M. Lee, and students in my lab for assistance with plant growth and data collection. The Editor and two reviewers provided comments that greatly improved a previous version of this manuscript. This work was supported by a Carnegie Trust Travel grant.