(C) 2012 Jeffery M. Saarela. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

Five species of the grass genus Spartina are invading salt marshes along the Pacific coast of North America, of which three have been documented in British Columbia, Canada, in only the last decade. A taxonomic synopsis of the two native (Spartina gracilis, Spartina pectinata) and five introduced Spartina taxa (Spartina anglica, Spartina alterniflora, Spartina densiflora, Spartina patens, Spartina ×townsendii) in the Pacific Northwest is presented to facilitate their identification, including nomenclature, a new taxonomic key, new descriptions for a subset of taxa, and representative specimens. Spartina ×townsendii is newly reported for the flora of British Columbia. The non-coastal species Spartina pectinata is reported from an urban site in British Columbia, the first confirmed report of the taxon for the province. Lectotypes are newly designated for Spartina anglica C.E. Hubb., Spartina maritima subvar. fallax St.-Yves, and Spartina cynosuroides f. major St.-Yves.

invasive grasses, voucher specimens, coastal habitats, Spartina, grass taxonomy, species identification

Spartina Schreb. (cordgrass) is a small grass genus of some fifteen species native to North America, South America, and the Atlantic coasts of Europe and Africa occurring in such coastal habitats as intertidal mud flats, estuaries, salt marshes, and inland in marshes, sloughs and dry prairie. Spartina includes several globally invasive species (e.g., Spartina alterniflora Loisel., Spartina anglica C.E. Hubb., Spartina densiflora Brongn.) that are rapidly altering salt marsh and estuary ecosystems (e.g.,

This taxonomic study was prompted by difficulties encountered in determining recent herbarium collections of invasive Spartina from British Columbia. Existing regional taxonomic resources do not include all taxa known in the province (

The purpose of this paper is to provide up-to-date taxonomic information for specimen-based identification of Spartina species in the Pacific Northwest. Although field-based identification of invasive Spartina taxa is possible, reliable determinations should be made or confirmed from specimens, as most of the diagnostic characters require magnification and careful, accurate measurements. Specimens should be deposited in herbaria, where they become part of the scientific record, are available for study by other scientists, and document the distributions of species in time and space. Voucher specimens for invasive plants such as Spartina are particularly important, as they provide the raw materials from which reliable and repeatable identifications can be made, and they contribute to long-term understanding of the distribution and spread of these new invaders. Unfortunately, herbaria often have relatively few specimens of weedy species, a situation recently documented for noxious weeds in Washington (

Here, I present a taxonomic synopsis of the two native and five introduced taxa of Spartina known from British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon (Spartina alterniflora, Spartina anglica, Spartina densiflora, Spartina gracilis Trin., Spartina patens, Spartina pectinata Link, and Spartina ×townsendii). I provide a new taxonomic key for the region, nomenclature for all taxa, including previously unpublished details on several type specimens and new lectotypifications, references to published illustrations that clearly show diagnostic characters, specimen citations, and notes on how to distinguish the taxa. New descriptions are given for the closely related and morphologically similar taxa Spartina alterniflora, Spartina anglica, and Spartina ×townsendii, and the aggressively invading Spartina densiflora, which has recently appeared in British Columbia. Spartina ×townsendii is newly reported from British Columbia. The descriptions and keys are based on study of specimens collected within and outside the region, in consultation with the global primary and secondary taxonomic literature; these data should be useful for distinguishing the taxa wherever they occur globally, including in Alaska where Spartina has not been reported but is anticipated to become a problem in the future (

Spartina is a member of the grass subfamily Chloridoideae Kunth ex Beilschm., one of six major lineages (subfamilies) in the grass PACMAD clade, which also includes the subfamilies Panicoideae Link, Arundinoideae Burmeist., Micrairoideae Pilg., Aristidoideae Caro and Danthonioideae H.P.Linder & N.P.Barker (reviewed in

Taxonomic revisions of Spartina have been produced by

Spartina has a base chromosome number of x = 10, and all species are polyploids (e.g.,

http://species-id.net/wiki/Spartina

Plants perennial, culms cespitose from knotty bases or solitary from conspicuous creeping rhizomes. Leaves cauline; sheaths open; ligules a line of hairs; blades flat to involute. Inflorescences with multiple branches (i.e., spikes) inserted along a main axis, branches usually alternate, appressed to spreading. Spikelets laterally compressed, one-flowered, arranged in two rows along two sides of a more or less triquetrous axis, disarticulating below the glumes. Glumes unequal, strongly keeled; lower glumes 1-veined, shorter than upper glumes and floret; upper glumes 1–6-veined, usually longer than the floret. Lemmas 1–3-veined, keeled, shorter than the paleas. Paleas 2-veined, thin and papery, longer than the lemma. Anthers 3. Styles 2. Caryopses linear. Base chromosome number, x = 10. Named from the Greek spartine, a cord made from Spartium junceum L.(Spanish Broom; Fabaceae), and probably applied to Spartina in reference to its tough leaves (

Key to native and introduced species of Spartina in British Columbia, Washington and Oregon

| 1 | Leaf blades distinctly scabrous on their margins; spikelets tightly appressed and strongly overlapping | 2 |

| – | Leaf blades glabrous on their margins (occasionally with a few scattered teeth, but teeth never abundant); spikelets weakly appressed and weakly overlapping | 5 |

| 2 | Culms growing in tufts (i.e., cespitose) from hard knotty bases, rhizomes absent, rarely short; branches appressed, usually not readily discernible within an inflorescence, not distinctly one-sided | Spartina densiflora |

| – | Culms growing from rhizomes; branches appressed, ascending, or spreading, readily discernible within an inflorescence, distinctly one-sided | 3 |

| 3 | Upper glumes distinctly awned, awns 3–8 mm long; blades 5–15 mm wide; ligules 1–3 mm long; branches pedunculate, rarely sessile | Spartina pectinata |

| – | Upper glumes unawned or short-awned, when present awns to 2 mm long; blades 0.5–8 mm wide; ligules 0.5–1 mm long; branches sessile, rarely pedunculate | 4 |

| 4 | Glume keels ciliate, hairs stiff, 0.5–0.8(–1) mm long; glumes with two inconspicuous lateral veins on one side of the keel; branches appressed to the main axis; most branches 3–6 mm wide; inflorescences 8–25 cm long; spikelets ovate to lanceolate; florets more or less equaling the upper glumes in length | Spartina gracilis |

| – | Glume keels scabrous, teeth 0.1–0.2 mm long; glumes with two conspicuous lateral veins on one side of the keel; branches appressed, ascending, or spreading from main axis; most branches 2–2.5 mm wide; inflorescences 3–15 cm long; spikelets linear lanceolate to ovate lanceolate; florets shorter than the upper glumes | Spartina patens |

| 5 | Spikelets 8–14(–16.5) mm long; branch rachises 0.4–1 mm wide between spikelets; glumes glabrous or weakly pubescent; leaf blades more or less erect, forming an angle 15–18° with the culm | Spartina alterniflora |

| – | Spikelets 14–25 mm long; branch rachises 1–2.2 mm wide between spikelets; glumes moderately to densely pubescent; leaf blades ascending to spreading, forming an angle 30–60° with the culm | 6 |

| 6 | Spikelets (15–)16.5–25 mm long; anthers 7–10 mm long, usually fully exserted at maturity; pollen fertile; ligules 1–3 mm long; upper glumes 3–6-veined, 13–22 mm long; glumes (weakly) moderately to densely pubescent with hairs 0.1–0.3 mm long, hairs to 0.6 mm long and usually denser proximally; calluses (1.5–)2–4.5 mm long; branches (3–)4–5(–6) mm wide | Spartina anglica |

| – | Spikelets 14–17.5 mm long; anthers 5–7(–8.5) mm long, not or incompletely exserted at maturity, indehiscent; pollen sterile; ligules 1–1.5 mm long; upper glumes 3-veined, 12.5–16.5 mm long; glumes weakly to moderately pubescent with hairs 0.1–0.2 mm long, occasionally to 0.6 mm long proximally; calluses 0.6–1.5(–2) mm long; branches (2.5–)3–4 mm wide | Spartina ×townsendii |

http://species-id.net/wiki/Spartina_alterniflora

Culms to 250 cm tall, rhizomatous. Sheaths glabrous; ligules 1–2 mm long; blades 5–63 cm long × 3–10 mm wide at base, usually flat proximally, involute distally, divergent from stems 15–18°, adaxial and abaxial surfaces glabrous, margins smooth, rarely with occasional scabrous teeth. Inflorescences (6–)11–33 cm long × (5–)6–10(–15) mm wide at midpoint, erect, with 3–9(–12) branches; branches (4)5–15 cm long × 2–4 mm wide, appressed to main axis or ascending, rachises 0.4–1 mm wide between spikelets, extending 1–20 mm beyond terminal spikelet. Spikelets 8–14(–16.5) mm long × 1–2 mm wide, alternate, weakly appressed, weakly or moderately overlapping, calluses 0.5–1.5 mm long. Glumes glabrous or weakly pubescent, when present hairs to 0.2 mm long, proximal hairs sometimes denser and longer to 0.5 mm, keels glabrous or ciliate, when present hairs to 0.3 mm long, margins glabrous; lower glumes 4–9 mm long × 0.2–0.5 mm wide, 1-veined, tips acute; upper glumes 7–14 mm long × 1–1.2 mm wide, 5–7-veined, tips acuminate or obtuse. Lemmas 7–12 mm long, glabrous or scabrous; paleas exceeding lemmas by up to 1 mm; anthers 3–6 mm long, yellow, exserted at maturity, dehiscent, pollen fertile. 2n = 62 (

Smooth cordgrass, Atlantic cordgrass, Atlantic smooth cordgrass.

The epithet alterniflora means alternating flowers.

Native to the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of North America from Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, to Texas, U.S.A. (

Spartina alterniflora is often misspelled in the literature as “Spartina alternifolia”. Spartina alterniflora was described from Bayonne in southwestern France (

Several introductions of Spartina alterniflora have occurred along the west coast of North America where it is not native. The species was reported in 1945 from a single estuarial location in Willapa Bay, Washington, where occasional plants had been observed since around 1911, and thought to have been introduced in the early twentieth century with oyster culture (

In Oregon, Spartina alterniflora has been reported from the Siuslaw River estuary and Coos Bay (

The only native Spartina taxon in California is Spartina foliosa, and by the 1990s it was known that Spartina alterniflora was in the process of competitively excluding Spartina foliosa (

Spartina alterniflora is not known from British Columbia, Canada.

Spartina alterniflora and the European species Spartina maritima are the parents of the sterile F1 hybrid Spartina ×townsendii; unsurprisingly, Spartina alterniflora is morphologically similar to Spartina ×townsendii and the amphidiploid Spartina anglica. It can be distinguished from these taxa by its shorter spikelets [8–14(–16.5) mm vs. 14–25 mm], narrower branch rachises [0.4–1 mm wide between spikelets vs. 1–2.2 mm wide], glumes glabrous or weakly pubescent [vs. glumes weakly to densely pubescent], and leaf blades erect, forming an angle of 15–18° with the culm [vs. leaf blades spreading, forming an angle of 30–60° with the culm]. Spikelets of Spartina alterniflora are shown in Fig. 1, and an exemplar specimen is shown in Fig. 2. Glumes in Spartina alterniflora vary from glabrous to pubescent (details on this variation are given in

Spikelets of Spartina alterniflora (U.S.A.: Washington, Pacific Co., Zika 18935, WTU). Bar = 3 mm. Photo: J.M. Saarela.

Photograph of a specimen of Spartina alterniflora collected at Ellsworth Creek Preserve, Pacific County, Washington, where the species is introduced (Zika et al. 18936, WTU). Image published with the permission of University of Washington Herbarium, Burke Museum.

There is considerable morphological variation in Spartina alterniflora throughout its native range with northern plants from Canada and Maine tending to have looser inflorescences, weakly overlapping spikelets, and less glume pubescence, and southern plants tighter inflorescences, more strongly overlapping spikelets, and more pubescent glumes. This variation has been recognized taxonomically in the past at the species and infraspecific levels; however,

CANADA. New Brunswick: Charlotte Co.:E of Biological Station, St. Andrews, 45°04'N, 67°03'W, Aug 1929, M.O.Malte 798/29 (CAN [CAN33914]); Grand Manan, Ross Island, 44°42'N, 66°48'W, 10 Aug 1927, C.A.Weatherby & U.F.Weatherby 5784 (CAN [CAN33957]); Grand Manan, Thoroughfare, 44°42'N, 66°48'W, 14 Aug 1944, C.A.Weatherby & U.F.Weatherby 7314 (CAN [CAN33913]). Gloucester Co.: Bathurst and vicinity, 47°37'N, 65°39'W, 2 Aug 1926, M.O.Malte 732 (CAN [CAN124678]). Restigouche Co.: Dalhousie, 48°04'N, 66°22'W, 4 Aug 1955, H.J.Scoggan 12682 (CAN [CAN240149]). Saint John Co.: St. John, 45°16'N, 66°04'W, 17 Aug 1877, J.Macoun 28971 (CAN [CAN33915]); Saints’ Rest Beach, on W side of St. John, St. John Harbour, NE of Lorneville, ca. 45°15'N, 66°02'W, 24 Aug 1975, P.M.Catling & S.M.McKay s.n. (CAN [CAN396499]). Westmoreland Co.: Moncton, 46°08'N, 64°46'W, 18 Sep 1912, M.O.Malte 108312 (CAN [CAN206832]); 1 mi E of Cape Bimet, 5 mi E of Shediac, 46°14'N, 64°27'W, 7 Aug 1981, M.Shchepanek & A.Dugal 3615 (CAN [CAN474764]). Newfoundland and Labrador: Chapel Island, Rocky Point, 3 mi SE of Summerford, 49°28'N, 54°45'W, 13 Aug 1977, M.J.Shchepanek & D.White 3051 (CAN [CAN436102]). St. Georges District, Stephenville Crossing, 48°31'N; 58°25'W, 4 Aug 1986, L.Brouillet & I.Saucier 86178 (CAN [CAN546706]); St. Georges, 48°31'11"N, 58°54'51"W, M.L.Fernald, K.M.Wiegand & J.Kittredge 2598 (CAN [CAN33900]); St. Georges, 48°31'11"N, 58°54'51"W, 4 Aug 1986, L.Brouillet & I.Saucier 86173 (CAN [CAN546843]). Port-au-Port District, West Bay Center, 4 Aug 1986, I.Saucier & A.Leduc 86185 (CAN [CAN546845]). Nova Scotia: Annapolis Co.:Granville, 44°47'02"N, 65°26'59"W, 18 Jul 1921, M.L.Fernald & N.C.Fassett 23294 (CAN [CAN33905]). Cape Breton Co.: Louisburg, Cape Breton, 18 Aug 1898, J.Macoun 21129 (CAN [CAN33902]). Digby Co.: Meteghan River, Clare Municipality, 44°13'N, 66°08'W, 27 Jul 1975, A.W.Dugal 75-66 (CAN [CAN475739]); Sissiboo River, Weymouth, 44°24'44"N, 65°59'43"W, 21 Aug 1920, M.L.Fernald, C.H.Bissell, C.B.Graves, B.Long & D.H.Linder 19972 (CAN [CAN33903]); Digby, 44°37'20"N, 65°45'38"W, 27 Aug 1910, J.Macoun 82104 (CAN [CAN33901]). Guysborough Co.:Canso, 45°20'12"N, 60°59'40"W, 15 Aug 1901, J.Fowler s.n. (CAN [CAN390991]); Canso, 45°20'12"N, 60°59'40"W, 1416 Aug 1930, J.Rousseau 35509 (CAN [CAN33907]); Guysborough, 45°23'N, 61°29'57"W, 6–7 Aug 1930, J.Rousseau 35357 (CAN [CAN33908]). Kings Co.: Avonport, 45°06'01"N, 64°15'27"W, 23 Jul 1957, H.J.Scoggan 13849 (CAN [CAN255571]). Lunenburg Co.: LaHave River, 44°17'37"N, 64°21'27"W, 6 Aug 1910, J.Macoun 82103 (CAN [CAN33904]). Pictou Co.: Pictou, 45°40'33"N, 62°42'33"W, 12 Aug 1880, McKay 28969 (CAN [CAN33906]); same locality, 31 Jul 1880, McKay 28972 (CAN [CAN33910]). Richmond Co.: Cape Breton Island, Richmond Municipality, Fullers River Salt Marsh, 3 km W of Fourchu, off Hwy. 327, 45°43'N, 60°18'W, M.J.Shchepanek & A.W.Dugal 6419 (CAN [CAN521694]). Queens Co.: N, end of Summerville Beach, Summerville Center, 43°57'N, 64°49'W, 28 Sep 1979, D.F.Brunton & H.L.Dickson 2092 (CAN [CAN452659]). Yarmouth Co.: Port Maitland, 43°59'03"N, 66°09'03"W, 24 Aug 1913, M.O.Malte s.n. (CAN [CAN206823]); Wedgeport, 43°42'58"N, 65°58'45"W, 18 Jul 1953, W.L.Klawe 1204 (CAN [CAN298544]); Lower Argyle, 43°43'44"N, 65°50'01"W, 11 Aug 1920, M.L.Fernald, C.H.Bissell, C.B.Graves, B.Long, D.H.Linder 19971 (CAN [CAN33909]). Prince Edward Island: Brackley Point, 46°23'N, 63°11'W, 4 Aug 1888, J.Macoun 28968 (CAN); Prince Co.: Tignish, 46°57'N, 64°02'W, 6 Aug 1912, M.L.Fernald, B.Long & H.St.John 6877 (CAN). Queens Co.: ¼ mi E of Pond Point, Long Creek salt marsh, 56°03'N, 62°57'W, M.Shchepanek & A.Dugal 4128 (CAN). Quebec: Bas-Saint-Laurent Region, Rocher blanc, 48°25'19"N, 68°36'24"W, 19 Jul 1949, Fr.Claude s.n. (CAN [CAN388720]); Cap a la Carre, St. Fabien, Gaspé, 48°17'N, 68°52'W, 9 Aug 1970, J.K.Morton NA3907 (CAN [CAN359898]); Cacouna Harbour development ca. 8 km NE of Rivière-du-Loup, 47°55'N, 69°30'W, 12 Aug 1980, D.F.Brunton 2519 (CAN [CAN455714]); Notre-Dame-du-Portage, 47°46'N, 69°37'W, 30 Aug 1970, G.Lemieux 13633 (CAN [CAN444192]); Rankin Point near Kamouraska, 24 Aug 1947, J.H.Soper & D.A.Fraser 3650 (CAN [CAN257673]). Capitale-Nationale Region, Baie-St.-Paul, 47°25'N, 71°20'W, 29 Jul 1984, S.G.Aiken 2962 (CAN [CAN484859]); Murray Bay, 47°38'60"N, 70°07'60"W, 14 Aug 1905, J.Macoun 68994 (CAN [CAN33921]). Côte-Nord Region, Anticosti Island, Ellis Bay, 49°30'N, 63°00'W, 7 Sep 1883, J.Macoun 28970 (CAN [CAN33920]); Betchwan [sic] [Betchouane], 50°14'27"N, 63°11'01"W, 25 Aug 1928, H.F.Lewis 130615 (CAN [CAN33919]); Havre des Canadiens, Natashquan, 50°10'59"N, 61°49'W, 7 Sep 1915, H.St.John 90141 (CAN [CAN33922]). Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine Region, Parc de Forillon, Penouille, 48°51'N, 64°26'W, 17 Jul 1971, M.M.Grandtner G158 (CAN); Magdalen Islands, Coffin Island, East Cape, 47°33'N, 61°31'W, 17 Aug 1912, M.L.Fernald, B.Long & H.St.John 6878 (CAN [CAN33918]); Coin du Banc, 48°33'28"N, 64°17'34"W, 31 Jul 1939, H.J.Scoggan 646 (CAN [CAN33916]); House Harbour, Alright Island, 47°25'59"N, 61°46'W, 17 Aug 1917, F.Johansen s.n. (CAN [CAN33917]); Carleton, 48°05'N, 66°08'W, 11 Aug 1930, F.Marie-Victorin, F.Rolland-Germain & E.Jacques 33291 (CAN [CAN513103]); Gaspé Peninsula, Bonaventure River, 48°03'N, 65°29'W, 12 Aug 1940, H.J.Scoggan 1214 (CAN [CAN220299]); près du pont de la Grosse Ile, Iles-de-la-Madeleine, 47°37'N, 61°33'W, 0.3 m, 7 Aug 1966, M.M.Grandtner 10801-V (CAN [CAN519301]). United States of America. Connecticut: New London Co.: Norwich, 41°31'N, 72°04'W, G.R.Lumsden s.n., 11 Aug 1885 (CAN [CAN162186]). Massachusetts: Barnstable Co.: Provincetown, Provincetown Harbor, 42°02'N, 70°10'W, 9 Oct 1988, S.G.Aiken & S.R.Johnstone 88-488 (CAN). Essex Co.: salt marsh between Briar Neck and Bass Rocks, Gloucester, 42°36'N, 70°39'W, 26 Aug 1945, L.B.Smith 1318 (CAN [CAN162185]); same locality, 42°36'N, 70°39'W, 19 Aug 1945, L.B.Smith 1317 (CAN [CAN162182]); Salem, 42°31'N, 70°53'W, 188-, J.Sears 47174 (CAN [CAN162187]). Maryland: seashore, Sep 1863, Wm.M.Canby s.n. (CAN [CAN162184, CAN162183]). Washington: Skagit Co.: Dike Island in Padilla Bay, 7 mi W of Mt. Vernon, 19 Nov 1964, R.G.Jeffrey 64-1 (US [US2580778]). Pacific Co.: Willapa Refuge, tide water marsh, 28 Sep 1945, M.L.Hinshaw s.n. (US [US1867453]); Willapa Bay, W and N Long Island, some five small patches, scattered, apparently spreading, 10 Aug 1942, W.G.McFarland s.n. (US [US2436000]); T1N R10W, Section 22, mouth of Naselle River at SE end of Hwy. 101 bridge, 46.4291°N, 123.9078°W, 16 Sep 2000, C.L.Maxwell 1575 (WTU [WTU342828], Suppl. Fig. 1); The Nature Conservancy’s Ellsworth Creek Preserve, mouth of Ellsworth Creek on S bank of Naselle River mouth, entrance to Yellow Gate Road, T11N R10W S22, 46°25.6'N, 123°53.675'W, 0 m, 4 Sep 2003, P.F.Zika, D.Giblin, S.Rodman et al. 18936 (WTU [WTU357790], Fig. 2); Willapa Bay, sea level, 15 Sep 1994, W.Lebovitz s.n. (WTU [WTU344373], Suppl. Fig. 2); below Bruceport County Park campground, T14N R10W S22, 46°41.4'N, 123°53.1'W, 3 Sep 2003, P.F.Zika 18935 (WTU [WTU371783], Suppl. Fig. 3). England. Hampshire Co.: Southampton, 50°53'49"N, 01°24'15"W, s.d., Dalington s.n. (CAN [CAN134028]). Isle of Wight Co.:Isle of Wight, ca. 50°40'51"N, 01°16'51"W, 9 Oct 1871, F.Stratton s.n. (CAN). France. Bayonne, 43°29'N, 01°28'W, s.d., collector illegible (CAN [CAN134029]); same locality, 43°29'N, 01°28'W, Sep 1899, E.Mouillefarine s.n. (CAN [CAN560721]); Biarritz, 43°29'N, 01°33'W, Oliver s.n. (CAN [CAN421008]); Landes, near Capbreton, 43°38'N, 01°25'E, 24 Jun 1954, A.E.Porsild 18851 (CAN [CAN244668]).

http://species-id.net/wiki/Spartina_anglica

Culms 32–104 cm tall, thick, fleshy, rhizomatous, forming clumps and dense swards. Sheaths glabrous, occasionally with short, scattered hairs, when present hairs to 0.2 mm long; ligules 1–3 mm long; blades 6–45 cm long × 4–10 mm wide, flat proximally, moderately to strongly involute distally, divergent 30–60° from culms, adaxial surfaces glabrous, occasionally sparsely pubescent proximally, when present hairs to 0.2 mm long, abaxial surfaces glabrous, occasionally sparsely pubescent proximally, when present hairs to 0.5 mm long, margins smooth. Inflorescences 12–21.5(–31.5) cm long × 7–25 mm wide at midpoint, erect, with (2)3–5(–11) branches; branches (7–)8–15(–20) cm long × (3–)4–5(–6) mm wide, appressed to main axis or ascending; rachises 1–2.2 mm wide between spikelets, extending 2–20 mm beyond the distal spikelet, glabrous, margins glabrous, occasionally sparsely pubescent, when present the hairs 0.2–0.4 mm long. Spikelets (15–)16.5–25 mm long × 1.8–2.5(–2.8) mm wide, weakly appressed, weakly overlapping, calluses (1.5–)2–4.5 mm long. Glumes (weakly) moderately or densely pubescent, hairs 0.1–0.3 mm long, hairs usually denser and to 0.6 mm long proximally; keels scabrous or ciliate, hairs to 0.5 mm long; lower glumes 8–14 mm long × 0.5–0.7 mm wide, 1-veined, tips acute or obtuse; upper glumes 13–22 mm long × 1–1.5 mm wide, 3–6 veined, tips obtuse or acute; lemmas 11–17 mm long, 1–3-veined, appressed pubescent distally, glabrous proximally, margins membranous; paleas exceeding lemmas by 1–2 mm; anthers 7–10 mm long, yellowish, usually fully exserted at maturity, dehiscent, pollen fertile. 2n = 120, 122, 124 (

English cordgrass; common cordgrass.

The Latin epithet anglica means English, given to the species in reference to England, its place of origin.

Britain, China (

Spartina anglica is an amphidiploid taxon that arose in Britain in the 18th century from chromosome doubling of the sterile F1 hybrid taxon Spartina ×townsendii (see the discussion under that species for details, and reviews in Marchant 1968 and

Spartina anglica is a problematic invasive species in coastal areas of western North America, and has been present on the continent for over fifty years. In the United States it is known from Washington and California. It was planted in Puget Sound, Washington in 1961 (

Spartina anglica was discovered in British Columbia in 2003 on Roberts Banks in the Fraser River estuary and in Boundary Bay along the British Columbia and Washington border (

Photograph of a specimen of Spartina anglica collected in Boundary Bay, south of Vancouver, British Columbia (

The description here is based on collections from Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia, and Old World material housed at CAN and UBC (see Specimens Examined). Spartina anglica is morphologically similar to Spartina ×townsendii, and the two can be challenging to distinguish. Differences between these species were characterized in detail by

Overall, plants of Spartina anglica tend to be larger than those of Spartina ×townsendii, including the lengths of reproductive structures useful in distinguishing the taxa. The species can be distinguished with careful measurements on herbarium specimens, though there is some overlap in the diagnostic morphological characteristics. When making a determination, multiple characters should be examined and multiple measurements should be made on a single plant when possible. Spartina anglica is distinguished from Spartina ×townsendii by its longer spikelets [(15–)16.5–25 mm long vs. 14–17.5 mm long]; longer anthers [7–10 mm long vs. 5–7(–8.5) mm long]; anthers that are fully exserted and dehiscent [vs. anthers that are not or incompletely exserted and indehiscent; Fig. 4]; fertile pollen [vs. sterile pollen (see below and Fig. 5)]; longer ligules [1–3 mm long vs. 1–1.5 mm long]; 3–6-veined upper glumes [vs. 3-veined upper glumes]; and longer upper glumes [13–22 mm long vs. 12.5–16.5 mm long].

Anthers of a Spartina anglica [U.S.A., Washington, Pacific Co., Zika 17595, WTU], bar = 3 mm. b Spartina ×townsendii [England, Hythe, Southampton, Marchant s.n., UBCV221074], bar = 3 mm. Anthers of Spartina anglica are fully exserted at anthesis, dehiscent, and the pollen is fertile. The longitudinal splitting of the anthers is a good indicator of dehiscence. Anthers in Spartina ×townsendii are not or incompletely exserted at anthesis, indehiscent, and the pollen is sterile. Photos: J.M. Saarela.

Spartina anglica can be distinguished from Spartina alterniflora by its longer spikelets [(15–)16.5–25 mm long vs. 8–14(–16.5) mm long], moderately to densely pubescent glumes (vs. glabrous or weakly pubescent glumes) and its longer anthers (7–10 mm long vs. 3–6 mm long). Spartina anglica is readily distinguished from Spartina densiflora, Spartina gracilis, Spartina patens and Spartina pectinata by its glabrous leaf blade margins [vs. scabrous leaf blade margins].

Determining pollen fertility by staining anthers with lactophenol cotton blue is a useful way to distinguish male sterile hybrid plants from those that are fertile, as the cytoplasm of fertile pollen grains readily takes up the stain whereas sterile (i.e., aborted) pollen grains do not. Pollen staining is thus an effective, though more technically involved method, to definitively distinguish the fertile Spartina anglica from the sterile F1 hybrid Spartina ×townsendii, as demonstrated by

Pollen stained with lactophenol cotton blue. a, b Spartina anglica, fertile pollen [Canada, British Columbia,

Canada. British Columbia: Greater Vancouver Regional District: Lower Fraser Valley, Boundary Bay, foot of 104th Street, 49°02'00"N, 122°56'00"W, 26 May 2004, P.Lim s.n. (V [V191319]); Lower Fraser Valley, Boundary Bay, foot of 112th Street, 49°02'00"N, 122°56'00"W, 16 Jun 2004, P.Lim s.n. (V [V191320]]); Delta, Boundary Bay Regional Park, off 12th Avenue, 49°00'N, 123°02'W, 30 Jul 2004, G.

http://species-id.net/wiki/Spartina_densiflora

Culms to 96 cm tall, cespitose from hard knotty bases, rarely with short rhizomes, forming dense tufts. Sheaths glabrous, often purple-tinged; ligules 1–2 mm long; blades to 32 cm long × 1–2 mm wide, involute for most or all of their length, wider proximally when flat, adaxial surfaces scabrous, abaxial surfaces glabrous, margins scabrous. Inflorescences 10.5–17 cm long × 6–8(–10) mm wide at midpoint, with (2–)6–9(–15) branches; branches 3–6(–7.5) cm long × 2–3 mm wide, appressed, conspicuously decreasing in length towards inflorescence apex, rachises 0.8–1 mm wide between spikelets, not extending beyond terminal spikelet, glabrous, margins glabrous or scabrous. Spikelets 9–13 mm long × 1.5–2 mm wide, tightly appressed, strongly overlapping; calluses 1–1.5 mm long. Glumes glabrous or scabrous, when present hairs < 0.1 mm long, keels scabrous, teeth 0.1–0.2 mm long, margins usually purple-tinged; lower glumes 4–7 mm long × 0.5–0.7 mm wide, 1-veined; upper glumes 7.5–11.5 mm long × 1–1.5 mm wide, 1-veined; lemmas 6–9 mm long, glabrous or minutely scabrous, keels scabrous distally, glabrous proximally; paleas exceeding lemmas by 0.5 mm, glabrous; anthers 3–4 mm long, yellowish, exserted at maturity, pollen fertile. 2n = 70 (

Austral cordgrass.

The epithet densiflora refers to the densely-flowered inflorescences of the species.

Native to South America in temperate coastal regions of southern Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, and on the coast of Chile (

The taxonomy, biogeography, and natural history of Spartina densiflora is reviewed by

In North America, Spartina densiflora is present in California, Washington, and British Columbia. It was first established in California. It occurs in Humboldt Bay, where it is thought to have been introduced by shipping in the late 1800s (

Spartina densiflora was documented in Washington a decade ago. The first collection was made in 2001 on Whidbey Island at the northern boundary of Puget Sound (Heimer 01-1 WTU, UBC).

Spartina densiflora is now invading British Columbia, where it was first found in 2005 in Bayne’s Sound, a channel between Vancouver Island and Denman Island (

Photograph of a specimen of Spartina densiflora collected at Fanny Bay, Vancouver Island, British Columbia (Lomer 5723, UBC). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

The description presented here is based on the few specimens that have been collected in Washington and British Columbia and deposited in herbaria (see Specimens Examined). Variation in some characters, particularly vegetative characteristics such as leaf length and culm height, is probably greater than recorded here. For example,

Spartina densiflora can be distinguished from Spartina alterniflora, Spartina anglica, and Spartina ×townsendii by the following combination of characters: plants cespitose [vs. strongly rhizomatous]; blades involute for all or most of their length [vs. blades flat proximally, involute distally]; blade margins scabrous [vs. blade margins smooth]; branch rachises not prolonged beyond the terminal spikelet [vs. branch rachises prolonged beyond the terminal spikelet as a bristle, rarely not prolonged]; glume margins often purple-tinged [vs. glume margins whitish, not purple-tinged] (Fig. 7); and spikelets tightly appressed and strongly overlapping, concealing the rachis between spikelets [vs. spikelets weakly appressed and weakly to moderately overlapping, with portions of the rachis usually visible between spikelets]. In the field, the leaf margins of Spartina densiflora may feel smooth to the touch, as the involute blades often conceal the leaf margins where the scabrous teeth are located; these scabrous teeth are best observed with a microscope (F. Lomer, personal communication, 2012). Spartina densiflora is readily distinguished from Spartina gracilis, Spartina patens, and Spartina pectinata by its cespitose habit [vs. rhizomatous].

Spikelets of Spartina densiflora (Canada, British Columbia, Lomer 5723, UBC). Bar = 3 mm. Photo: J.M. Saarela.

Canada. British Columbia: Vancouver Island, Fanny Bay, 500 m N of Waterloo Creek, 49°28.572'N, 124°47.494'W, 24 August 2005, F.Lomer 5723 (UBC, Fig. 6); Vancouver Island, 20 km south of Courtenay, Buckley Bay Ferry Terminal, north side of dock at high tide level, single clump, sea level, 49°31'32"N, 124°50'54.5"W, 12 July 2010, F.Lomer 7377 (CAN, Suppl. Fig. 23). United States of America. Washington: Island Co.: Whidbey Island, near Coupeville (T32E R2E S37), 14 Nov 2001, D.Heimer 01-01 (UBC [UBCV224048, Suppl. Fig. 24], WTU [WTUb349303, Suppl. Fig. 25]).

http://species-id.net/wiki/Spartina_gracilis

See

Alkali cordgrass, big cordgrass.

The Latin epithet gracilis means “thin, slender” (

Southern Northwest Territories, Canada, to central Mexico (

Spartina gracilis is a distinctive taxon (Fig. 8). In the Pacific Northwest it is likely to be most readily confused with Spartina pectinata, which also grows inland. It is distinguished from Spartina pectinata by the following combination of characters: upper glumes unawned or short-awned, awns to 2 mm long [vs. distinctly awned upper glumes, awns 3–8 mm long], ciliate glume keels [vs. pectinate glume keels], spikelets 6–11 mm long [vs. 10–25 mm long], ligules 0.5–1 mm long [vs. 1–3 mm long], 3–12 branches per inflorescence [vs. 5–50 branches per inflorescence], and 10–30 spikelets per branch [vs. 10–80 spikelets per branch]. It is distinguished from Spartina patens by its ciliate glume keels [vs. scabrous glume keels], inconspicuous lateral veins on the upper glumes [vs. conspicuous lateral veins on the upper glumes], most branches 3–6 mm wide [vs. most branches 2–3 mm wide], branches closely appressed to the main axis [vs. branches appressed, ascending or spreading from main axis], and florets more or less equaling the upper glumes in length [vs. florets shorter than the upper glumes]. Spartina gracilis can be readily separated from Spartina alterniflora, Spartina anglica and Spartina ×townsendii by its scabrous leaf margins [vs. glabrous leaf margins], and from Spartina densiflora by its rhizomatous habit [vs. cespitose].

Photograph of a specimen of Spartina gracilis collected in the Thompson River Valley, British Columbia (Scoggan 15626, CAN).

CANADA. British Columbia: 23 mi W of Kamloops, 50.6667°N, 120.8569°W uncertainty 33215 m, 23 July 1941, W.A.Weber 2548 (CAN [CAN33940]); Thompson River valley between Spences Bridge and Cache Creek, 50.6059°N, 121.3386°W uncertainty 22 km, 15 July 1964, H.J.Scoggan 15626 (CAN [CAN308046], Fig. 8); Flying U Ranch, Cariboo, bank at edge of Green Lake, 51.4172°N, 121.2025°W uncertainty 8569 m, 21 June 1944, J.W.Eastham 11509 (CAN [CAN33941]); N of Kamloops, 50.6667°N, 120.3333°W uncertainty 7196 m, 13 Jun 1889, J.Macoun s.n. (CAN [CAN33943, Suppl. Fig. 26]); Kamloops, 50.6667°N, 120.3333°W uncertainty 7196 m, 4–7 Sep 1931, V.Kujala & A.Cajander s.n. (CAN [CAN394081, CAN394014, Suppl. Fig. 27]); 119 mile, Cariboo, 18 Jun 1942, J.A.Munro 23 (CAN [CAN33942]); Similkameen River, 10 Jun 1905, J.M.Macoun 77227 (CAN [CAN33944, Suppl. Fig. 28]). UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. Montana: Hound Creek, 30 Jul 1883, F. Lamson-Scribner 329 (CAN [CAN162196]). North Dakota: Ward County, 26 Jul 1963, L.F.Lautenschlager 694 (CAN [CAN297003]). Utah: Death Ridge-Horse Mountain Road, near Caanan Peak, 6800 ft, 15 June 1990, M.A.Franklin & D.Atwood 7129 (CAN[CAN563733]). Washington: Okanogan Co.: Loomiston, Aug 1897, A.D.E.Elmer 891 (CAN [CAN162194, CAN162191]).

http://species-id.net/wiki/Spartina_patens

See

Saltmeadow cordgrass, saltmeadow grass, marsh hay, wiregrass, foxgrass, couchgrass, rush saltgrass, spartine étalée (

The Latin epithet patens means “spreading, outspread” (

Native to the east coast of North America and Central America, distributed along the Atlantic coast of Newfoundland and Labrador to Texas, the Atlantic coast of Mexico, and throughout the Caribbean Islands (e.g.,

Spartina patens grows in coastal salt marshes and brackish waters, where it usually forms dense stands above the intertidal zone and into higher and drier areas of the salt marsh (

In Oregon, Spartina patens grows in the Siuslaw estuary on Cox Island (Lane Co.), where it has been introduced since at least 1939 and has expanded considerably since that time (

Spartina patens was the first of the invasive cordgrasses to be collected in British Columbia. It was discovered in 1979 in the Comox Estuary on Vancouver Island (Brayshaw 79-1143, V); nearly a decade later, in 1988, it was collected on the adjacent mainland coast in Burrard Inlet, North Vancouver (Lomer 88–140, UBC, Fig. 9). Spartina patens was recognized as part of the provincial flora by

Photograph of a specimen of Spartina patens collected at Maplewood mudflats, North Vancouver, British Columbia (Lomer 88–140, UBC). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Spartina patens exhibits considerable morphological variation and several authors have recognized two infraspecific taxa (see

Based on specimens of Spartina patens examined here collected in Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia, introduced plants in these areas are similar morphologically to those in the eastern Canada and the northeastern United States, which tend to be smaller than plants distributed further south (

Spartina patens can be distinguished from Spartina densiflora by the following combination of characters: branches distinctly one-sided, appressed, ascending or spreading from main axis, distant or weakly overlapping, and approximately the same length within an inflorescence [vs. branches not distinctly one-sided, appressed, strongly overlapping, and conspicuously decreasing in length towards the inflorescence apex], rhizomes wiry, plants forming dense mats [vs. rhizomes absent, rarely short, plants cespitose, forming distinct clumps], upper glumes distinctly 3-veined [vs. upper glumes 1-veined], and ligules 0.5–1 mm long [vs. ligules 1–2 mm long].

Spartina patens can be distinguished from Spartina alterniflora, Spartina anglica and Spartina ×townsendii by: blade margins and adaxial surfaces scabrous [vs. blade margins and adaxial surfaces glabrous], blades 0.5–4 mm wide at base, involute for most or all of their length [vs. blades 3–10 mm wide at base, often involute distally], branches distinctly one-sided, distant or weakly overlapping [vs. branches not distinctly one sided, strongly overlapping], rhizomes thin and wiry [vs. rhizomes thick and fleshy], upper glumes conspicuously 3-veined [vs. upper glumes 1–3-veined, veins inconspicuous], and spikelets usually purple-tinged [vs. spikelets rarely or never purple-tinged].

Canada. British Columbia: Vancouver Island, Goose Spit, Comox, 49°40'N, 124°54'W, 14 Sep 1979, T.C.Brayshaw 79-1143 (V [V95308]); Vancouver Island, based of Comox Spit, 49°40'N, 124°54'W, 7 Aug 1984, T.C.Brayshaw 84-139 (V [V127117]); N shore of Burrard Inlet, E of Second Narrows Bridge, North Vancouver, 49.3099°N, 123.1032°W uncertainty 4052 m, sea level, Jul 1987, F.Lomer 87-001 (UBC [UBCV194265, Suppl. Fig. 29]); North Vancouver, Maplewood Mudflats, S of Dollarton Highway and E of Second Narrows bridge, 49.3042°N, 123.0009°W uncertainty 500 m, 27 Aug 1988, F. Lomer 88-140 (UBC [UBCV195726, Fig. 9); North Vancouver, Maplewood mud flats, 49.3042°N, 123.0009°W uncertainty 500 m, 16 Sep 1993, F.Lomer s.n. (V [V169504, V169505]). New Brunswick: St. Andrew’s, 16 Aug 1900, J.Fowler s.n. (CAN [CAN390994]). Charlotte Co.: Grand Manan, 44°41'53"N, 66°49'20"W, 31 Jul 1944, C.A.Weatherby & U.F.Weatherby 7300 (CAN [CAN33948]). Westmorland Co.: 1 mi E of Cape Bimet, 5 mi E of Shediac, 46°14'N, 64°27'W, 7 Aug 1981, M.Shchepanek & A.Dugal 3657 (CAN [CAN474807]); W of upper cape, 7 Aug 1964, P.R.Roberts & N.Bateman 64-2564 (CAN [CAN305984]); Memramcook, 45°58'15"N, 64°35'36"W, 21 Aug 1919, F.Rolland-Germaine 8022 (CAN [CAN332081]); Shediac, 46°13'17"N, 64°32'23"W, 5 Aug 1904, J.Fowler s.n. (CAN [CAN391711]); Moncton, 46°05'58"N, 64°47'59"W, 18 Sep 1912, M.O.Malte 108313 (CAN [CAN206830]). Restigouche Co.: Dalhousie, 48°2'55"N, 66°23'25"W, 4 Aug 1955, H.J.Scoggan 12683 (CAN [CAN240148]). Newfoundland and Labrador: Bonavista South District, Newman Sound Marsh, 48°32'15"N, 53°58'06"W, R.Charest, L.Brouillet, A.Bouchard & S.Hay 96-2065 (CAN [CAN58446]); St. George’s, 48°24'55"N, 58°29'40"W, 13 Aug 1910, M.L.Fernald & K.M.Wiegand 2597 (CAN [CAN33945]); St. George’s District, St. George’s, 48°24'55"N, 58°29'40"W, 4 Aug 1986, L.Brouillet & I.Saucier 86170 (CAN [CAN546790]; St. George’s District, Stephenville Crossing, saltmarsh NE of Main Gut bridge, 48°31'44"N, 58°27'19"W, 4 Aug 1986, L.Brouillet & I.Saucier 86183 (CAN [CAN546704]. Nova Scotia: N end of Summerville Beach, Summerville Center, 43°57'N, 64°49'W, 28 Sep 1979, D.F.Brunton & H.L.Dickson 2089 (CAN [CAN452656]; LeHave River, 6 Aug 1910, J.Macoun 82102 (CAN [CAN33949]. Cape Breton Co.: Grand Narrows, 45°57'24"N, 60°47'32"W, 27 Jul 1893, J.Macoun 21127, (CAN [CAN33952]); near mouth of George River, 27 Aug 1920, C.H.Bissell & D.H.Linder 19976 (CAN [CAN33951]. Digby Co.: Clare Municipality, Meteghan River, 44°13'N, 66°08'W, 30 Jul 1975, A.W.Dugal 75-131 (CAN [CAN475807]; Sissiboo River, Weymouth, 44°24'44"N, 65°59'43"W, 21 Aug 1920, M.L.Fernald, C.H.Bissell, C.B.Graves, B.Long & D.H.Linder 19974 (CAN [CAN33950]. Guysborough Co.: Canso, 45°20'12"N, 60°59'40"W, 15 Aug 1901, J.Fowler s.n. (CAN [CAN391709]. Hants Co.: mouth of Rennie Brook, East Walton, 17 Sep 1958, E.C.Smith, W.J.Curry, R.E.Clattenburg 18581 (CAN [CAN296579]). Kings Co.: Avonport, 45°06'01"N, 64°15'27"W, 23 July 1957, H.J.Scoggan 13850 (CAN [CAN255570]. Queens Co.: Port Mouton, 43°55'38"N, 64°50'55"W, C.H.Bissell & C.B.Graves 19978 (CAN [CAN33953]. Richmond Co.: Cape Breton Island, Fullers River Salt Marsh, 3 km W of Fourchu, off Hwy. 327, 45°43'N, 60°18'W, 23 Aug 1984, M.J.Shchepanek & A.W.Dugal 6426 (CAN [CAN521701]). Shelbourne Co.: Gunning Cove, 43°41'30"N, 65°20'45"W, 4 Oct 1982, S.J.Darbyshire 1790 (CAN [CAN487055]. Yarmouth Co.: Wedgeport, 43°44'23"N, 65°58'48"W 31 July 1953, W.L.Klawe 1278 (CAN [CAN298545]; Sand Beach, 43°48'43"N, 66°07'15"W, 7 Sep 1920, M.L.Fernald, B.Long, D.H.Linder 19977 (CAN [CAN33954]. Ontario: Essex Co.: Windsor, Windsor Salt Factory, 42°17'N, 83°06'W, 21 Sep 1975, P.M.Catling & S.M.McKay s.n. (CAN [CAN396523]); Windsor salt works, 24 Aug 1977, W.Botham 2011 (CAN [CAN459521], CAN [CAN459519]); Windsor, near salt factory, 29 Jul 1979, W.Botham 2182 (CAN [CAN459520]); Windsor, E side of Euclid Avenue bordering Detroit River, just S of Prospect Street, Ojibway Park, near salt plant, 42°17'N, 83°05'W, 3 Nov 1975, P.D.Pratt 18 (CAN [CAN440539]); Windsor, 50 m W of Prospect Avenue, along Euclid Road, E shore Detroit River, 42°17'N, 83°05'W, 4 Sep 1979, D.F.Brunton & P.D.Pratt 1915 (CAN [CAN452513]). Prince Edward Island: Prince Co.: Tignish, 46°57'02"N, 64°02'01"W, 6 Aug 1912, M.L.Fernald, B.Long & H.St-John 113172 (CAN [CAN33946]). Queens Co.: Long Creek salt marsh, ¼ mi E of Pond Point, 46°03'N, 62°57'W, 15 Aug 1981, M.Shchepanek & A.Dugal 4119 (CAN [CAN475274]); Brackley Point, 46°23'04"N, 63°11'06"W, 3 Aug 1888, J.Macoun 28967 (CAN [CAN33947]). Quebec: Maria Co.: Bonaventure, 48°03'N, 65°29'W, 11 Aug 1930, F.Marie-Victorin, F.Rolland-Germaine & E.Jacques 33799 (CAN [CAN33955]); Magdalen Islands, sandy sea strand at the Narrows, Alright Island, 21 Aug 1912, M.L.Fernald, B.Long & H.St-John 6880 (CAN [CAN33956]); Rivière-du-Loup Co.: Pointe-à-la-Loupe, L’Isle-Verte, 48°4'38"N, 69°16'28"W, 2 Sep 1957, E.Lepage 13956 (CAN [CAN252814]); Rivière-du-Loup, Hwy. 20, N shore of bay, 47°49'N, 69°32'W, 29 Sep 1979, H.L.Dickson & D.F.Brunton 3271 (CAN [CAN457594]). Kamouraska Co.: Rankin Point near Kamouraska, 24 Aug 1947, J.H.Soper & D.A.Fraser 3647 (CAN [CAN257674]); Rimouski Co.: Rimouski, 48°27'N, 68°32'W 30 Sep 1950, E.Lepage 13215 (CAN [CAN206869]); Le Bic, Cap aux Corbeaux, 48°23'N, 68°43'W, 30 Aug 1970, G.Lemieux 13630 (CAN [CAN444255]); L’Isle-Verte, 48°01'N, 69°20'W, 24 Aug 1951, L.McI.Terrill s.n. (CAN [CAN337522]); Tobin, 23 Aug 1951, L.McI.Terrill 6636 (CAN [CAN337521]); Iles-de-la-Madeleine, Cap de l’Est, 47°36'47"N, 61°27'35"W, s.d., M.M.Grandtner s.n. (CAN [CAN519307]); Dune du Nord, près de la Grande Lagune, 47°29'N, 61°45'W, 66.08.06, M.M.Grandtner 10697-V (CAN [CAN519268]); Ile-aux-Coudres, La Baleine, pointe E de l’île, 25 Aug 1977, J.Cayouette J77-133 (CAN [CAN466657]). United State of America. Florida: near Jacksonville, 17 Jul 1894, A.H.Curtiss 4948 (CAN [CAN373389]). Louisiana: Cameron Parish, along the Gulf of Mexico, S of an unnamed shell road which runs E from Cameron Parish Road 3106, on the E edge of Cameron, T15S, R9W, 30 Jun 1984, B.E.Button & D.W.Pritchett 2536 (CAN [CAN495018]); Jefferson Parish, roadside at Elmer’s Island, 2 Oct 1976, J.Guider 5023 (CAN [CAN432238]). Maryland: sea coast, Sep 1863, Wm.M.Canby s.n. (CAN [CAN162200]). Massachusetts: Barnstable Co.: Sandy Meck, Cape Cod, 41°44'00"N, 70°19'58"W, 28 Oct 1939, J.H.Soper 1109 (CAN [CAN257821, CAN316382]). Dukes Co.: Katama Bay, Edgartown, Marthas Vineyard, 41°21'15"N, 70°28'58"W, 11 Sep 1901, M.L.Fernald s.n. (CAN [CAN162201]). New Jersey: Atlantic City, 1880, C.D.Fretz s.n. (CAN [CAN556282]). New York: Nassau Co.:Jones Beach, 40°35'40"N, 73°30'10"W, 18 Aug 1932, H.A.Gleason & A.C.Smith 149 (CAN [CAN162198]). Washington: Jefferson Co.: mouth of Dosewallips River, E of Route 101, SW of Sylopash Point, 1 m, T25N R2W S2, 47°41.4'N, 122°53.5'W, 9 Sep 2004, P.F.Zika & F.Weinmann 20160 (WTU [WTU359724, Suppl. Fig. 30]). Oregon: Lane Co.: Cox Island, Siuslaw Estuary, 2.5 km E of Florence, 43.9716°N, 124.0672°W, 9 Aug 1983, R.E.Frenkel 3060 (UBC [UBCV196070, Suppl. Fig. 31]); Lane Co.: center of Cox Island in Siuslaw River estuary, 3.5 km E of Florence, SW corner Sec 30, T. 18S, R. 11 W., W.M., 43.9716°N, 124.0672°W, 22 Oct 1977, R.E.Frenkel s.n. (WTU [WTU286900, Suppl. Fig. 32]).

http://species-id.net/wiki/Spartina_pectinata

See

Prairie cordgrass.

The epithet pectinata means comb-like or tooth-like, and was given in reference to the distinctly pectinate teeth on the glume keels of Spartina pectinata, one of its diagnostic characteristics.

Spartina pectinata is widespread across much of North America north of Mexico, distributed in southern Alberta, eastern Washington and Oregon, south to Texas, and east to Newfoundland and Labrador (

Spartina pectinata is not considered to be a problematic invasive species, though it has been introduced sporadically to other regions, such as the United Kingdom. It occurs natively in eastern Washington and Oregon (

British Columbia is the only Canadian province in which Spartina pectinata is not native, but the taxon has been variously recognized as part of its flora. In the first major treatment of the British Columbia flora, Joseph K.

Photograph of a specimen of Spartina pectinata collected in Burnaby, British Columbia (Lomer 6778, UBC). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Spartina pectinata is readily distinguished from all other taxa in the Pacific Northwest by its conspicuously awned glumes [vs. glumes unawned or short-awned (awns to 2 mm long), the latter state sometimes present in Spartina gracilis], and glume keels with robust, comb-like teeth [vs. glume keels that are glabrous, scabrous or ciliate]. Additional characters are given under other taxa.

CANADA. British Columbia: Greater Vancouver, Burnaby, Canada Way and Wedgewood St., NE corner, vacant lot of demolished home, 49°13'30"N, 122°56'30"W, 130 m, 01 Sep 2008, F.Lomer 6778 (UBC [UBCV227607, Fig. 10]); same location, 15 Sep 2008, F.Lomer 6805 (UBC [UBCV227406, Suppl. Fig. 33]). Manitoba: Rural Municipality of Pembina, NE of Darlingford and E of Manitou, 49°14'12"N, 98°18'04"W, 437 m, 16 Jul 2007, J.M.Saarela 1019 (CAN [CAN590577]). United States of America. Colorado: Fort Collins, 3 Aug 1898, n.c. 3551 (CAN [CAN162205]). Idaho: Oneida Co.: American Falls, 28 Jul 1911, A.Nelson & J.F.Macbride 1394 (CAN [CAN162207]). Kansas: S of Quinter, 16 Oct 1937, C.Brown s.n. (CAN [CAN162202]). Maine: Aroostook Co.: valley of the St. John River, Big Black River Rapids, Township xv, Range 13, 26 Jul 1917, H.St.John & G.E.Nichols 2135 (CAN [CAN162203]). Minnesota: Kittson Co.: Hallock, 16 Jul 1986, F.W.Schueler 16461 (CAN [CAN536117]). St. Louis Co.: beach of Esquagama Lake, 4 Aug 1944, O.Lakela 5647 (CAN [CAN162197]). New Hamsphire: Rockingham Co.: Newfields, along Squamscott River below bridge to Stratham, 8 Aug 1973, A.R.Hodgden & F.L.Steele 19838 (CAN [CAN555731]). Strafford Co.: Milton, edge of pond by railroad, 15 Jul 1959, A.R.Hodgden & F.L.Steele 11095 (CAN [CAN555851]). New York: Madison Co.: shore of Oneida Lake, South Bay, 27 Jun 1921, H.D.House 8289 (CAN [CAN162204]); St. Lawrence Co.: Morristown, 44°35'08"N, 75°38'53"W, 15 Aug 1914, O.P.Phelps 156 (CAN [CAN162209]). North Dakota: Lamoure Co.: along creek ½ mil W, 2 ¼ mi N of Edgeley, Nora Township, 46°21'34"N, 98°42'44"W, 24 Aug 1937, J.H.Moore & M.Moore 10094 (CAN [CAN198696]). Ohio: Lucas Co.: SE corner of Monclova Township, low bank of Maumee River at SW corner of Maumee city limits, 10 Sep 1967, R.L.Stuckey 5782 (CAN [CAN320720]). Oregon: Bars of Snake River, Ballard’s Landing, 8 Jul 1899, Wm.C.Cusick 2221 (CAN [CAN162206]). South Dakota: Aberdeen, Aug 1969, S.N.Stephenson s.n. (CAN [CANB432790]).

http://species-id.net/wiki/Spartina_×townsendii

Culms 46–100 cm tall, thick, fleshy, rhizomatous. Sheaths glabrous; ligules 1–1.5 mm long; blades 6.5–37 cm long × 4–10 mm wide, flat proximally, often involute distally, divergent 30–40° from culms, adaxial surfaces glabrous, occasionally with very sparse hairs proximally, when present hairs to 0.2 mm long, abaxial surfaces glabrous, occasionally with sparse hairs proximally, when present hairs to 0.5 mm long, margins smooth. Inflorescences 10.5–24(–36) cm long × 7–25 mm wide at midpoint, erect, with (2)3–6(–10) branches; branches (6–)7.5–15(–18) cm long × (2.5–)3–4 mm wide, appressed or ascending, rachises 1–1.9 mm wide between spikelets, extending 2–10(–18) mm beyond the terminal spikelet, extension occasionally absent, glabrous, margins glabrous, occasionally with a few marginal hairs, when present hairs to 0.2 mm long. Spikelets 14–17.5 mm long × 1.5–2.5 mm wide, weakly appressed, weakly overlapping, calluses 0.6–1.5(–2) mm long. Glumes weakly to moderately pubescent, hairs 0.1–0.2 mm long, proximal hairs occasionally to 0.6 mm long, keels glabrous, ciliate or scabrous, when present hairs and teeth 0.2–0.5 mm long, usually longest proximally; lower glumes 7–13 mm long × 0.5–0.7 mm wide, 1-veined, tips acuminate or obtuse; upper glumes 12.5–16.5 mm long × 1–1.5 mm wide, 3-veined, tips acuminate or obtuse. Lemmas 9.5–13.5 mm long, 1-3–veined, pubescent distally, glabrous proximally, margins membranous, keels ciliate distally, hairs to 0.2 mm long, glabrous proximally. Paleas exceeding lemmas by ca. 1 mm, glabrous. Anthers 5–7(–8.5) mm long, not or incompletely exserted at maturity, indehiscent, medium to dark brown, pollen sterile; caryopses absent. 2n = 62 (

Townsend’s cordgrass.

The epithet townsendii was given in honour of the English botanist Frederick Townsend (1822–1905).

This species is found in England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland (

In the mid to late 1800s an unknown cordgrass of restricted distribution appeared and spread rapidly along the shores of Southampton Water, England (

Soon after its formal description Spartina townsendii was considered to be a species of hybrid origin.

An independent origin of Spartina ×townsendii is documented in France. In 1894 Jules Foucaud described Spartina neyrautii Fouc. from southwestern France and northern Spain. Spartina neyrautii was initially considered to be a variant of Spartina maritima (e.g., Chevalier 1923,

Spartina ×townsendii has been introduced into North America, where apparently only a single occurrence has been reported in the literature.

Spartina ×townsendii has not previously been reported from British Columbia. It is here reported as new for the province on the basis of two collections made in 2006 in in Boundary Bay at sites separated by some 4.4 kilometers (by air)[Taylor 80 (UBC, Fig. 11) and Saarela & Percy 791 (CAN, Fig. 12, UBC, Suppl. Fig. 34)]. These appear to be the most recent confirmed reports of the taxon in North America since it was collected at Stanwood, Washington. Herbarium specimens of these collections were initially determined (incorrectly) as Spartina anglica and Spartina alterniflora, since Spartina ×townsendii was not expected in British Columbia. Subsequent study of this material, in combination with the Spartina taxonomic literature and comparisons with specimens of Spartina anglica and Old World specimens of Spartina ×townsendii at CAN and UBC, confirmed the specimens to be Spartina ×townsendii, prompting the current taxonomic study. Pollen in these specimens is sterile, as determined by pollen staining (see discussion under Spartina anglica, Fig. 5), further confirming their identities as Spartina ×townsendii. Specimens from which pollen was extracted and stained with lactophenol cotton blue to assess fertility are identified with the symbol † in the Specimens Examined below.

Photograph of a specimen of Spartina ×townsendii collected in Boundary Bay, British Columbia (Taylor 80, UBC). This is the first record of the taxon for British Columbia. Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Photograph of a specimen of Spartina ×townsendii collected in Boundary Bay, British Columbia (Saarela and Percy 791, CAN). This is the second record of the taxon for British Columbia.

The origin of Spartina ×townsendii in British Columbia is not known, and there are no data on the extent of the Boundary Bay sub-populations in 2006 aside from notes on the Saarela and Percy collection label indicating a single clump of the grass approximately one meter in diameter. It is not known if Spartina ×townsendiihas persisted in British Columbia since collected some five years ago. Since major efforts are ongoing to remove Spartina plants from Boundary Bay where Spartina ×townsendiiwas found, it is possible the original stands from which the specimens were collected have been removed. The region should be studied to determine if the taxon is present. Since the taxon is sterile and does not set seed, it must have been introduced into Boundary Bay by vegetative reproduction, probably from rhizome fragments transported in tidal currents. It is possible that the British Columbia plants originated from the stand at Stanwood, Washington, if it persists, or there may be other extant occurrences of Spartina ×townsendii somewhereto the south of Boundary Bay. Workers searching Puget Sound for invasive Spartina (e.g.,

The description here is based on the first known collection from Washington, the two collections from British Columbia, and Old World material housed at CAN and UBC (see Specimens Examined), including collections made by H. & J. Groves who first described the taxon over a century ago. The North American specimens of Spartina ×townsendii are morphologically similar to the Old World specimens examined. Spartina ×townsendii is distinguished from Spartina anglica by its shorter spikelets [(14–17.5 mm long vs. (15–)16.5–25 mm long]; shorter anthers [5–7(–8.5) mm long vs. 7–10 mm long]; indehiscent anthers that are not or incompletely exserted with sterile pollen [vs. dehiscent anthers that are usually fully exserted with fertile pollen; see Figs 4, 5]; shorter ligules [1–1.5 mm long vs. 1–3 mm long]; upper glumes 3-veined [vs. upper glumes 3–6-veined]; and shorter upper glumes [12.5–16.5 mm long vs. 13–22 mm long]. The angle of the leaf blade with the stem is 30–40° in Spartina ×townsendii, compared to 30–60° in Spartina anglica (

Canada. British Columbia: Greater Vancouver Regional District: Boundary Bay Regional Park, Boundary Bay, S of Richmond along trail off 12 Avenue in Tsawwassen, near 1st viewing platform, 49°01'28"N, 123°03'14"W, ca. 0 m, 28 Nov 2006, J.M.Saarela & D.M.Percy 791 (CAN [CAN590439†, Fig. 12, UBC [UBCV228476†, Suppl. Fig. 34]); Greater Vancouver in marsh close to Undersea marshes and Pacific Flyway displays, Boundary Bay, 49°03'34"N, 123°01'27"W [secondary], 8 Nov 2006, T.Taylor 80 (UBC [UBCV222939†, Fig. 11). United States of America. Washington: Snohomish Co.:near Stanwood, ca. 48°14'N, 122°21'W, 26 Aug 1965, H.M.Austenson s.n. (WTU [WTU229915†, Suppl. Fig. 35]). England. Hampshire Co.: Hythe, South Hants, 9 Oct 1883, H.Groves s.n. (US [US555778]); Hayling Island, 13 Sep 1900, E.S.Marshall s.n. (CAN [CAN585633, Suppl. Fig. 36]); Southampton, 50°53'49"N, 01°24'15"W, Sep 1904, H.Groves & J.Groves 4596 (CAN [CAN251679†, Suppl. Fig. 37], US [US1535531]); Lymington, Keyhaven, 50°47'N, 00°58'W, 28 Aug 1977, G.Halliday 457/77 (CAN [CAN522593†, Suppl. Fig. 38]); Keyhaven, 50°43'22"N, 01°34'10"W, 30 Jul 1966, G.Halliday 100/66 (CAN [CAN301583, Suppl. Fig. 39]); Hants, Aug 1877, J.Groves s.n. (CAN [CAN421009†, Suppl. Fig. 40]); Hythe, Southampton, central marshes, male sterile, 50.8667°N, 01.3999°W uncertainty 7193 m, 10 Sep 1959, C.Marchant s.n. (UBC [UBCV221074, Suppl. Fig. 41]); N Hayling Island, Duckard Point, male sterile, 50.8051°N, 0.9778°W uncertainty 7194 m, 4 Aug 1960, C.Marchant s.n. (UBC [UBCV221101, Suppl. Fig. 42]); N Hayling Island, male sterile, 50.8051°N, 0.9778°W uncertainty 7194 m, 17 Aug 1961, C.Marchant s.n. (UBC [UBCV221098, Suppl. Fig. 43]); Eling, male sterile, 50.8999°N, 1.4833°W uncertainty 7193 m, 29 Aug 1961, C.Marchant s.n. (UBC [UBCV221100, Suppl. Fig. 44, UBC221095, Suppl. Fig. 45]); Hythe, south marshes, male sterile, 50.8666°N, 1.3999°W uncertainty 7193 m, 28 Oct 1959, C.Marchant s.n. (UBC [UBCV221093, Suppl. Fig. 46, UBCV221099, Suppl. Fig. 47]); Hythe, central marsh, near Sylvan Villa, giant male sterile, 50.8666°N, 1.3999°W uncertainty 7193 m, 16 Aug 1961, C.Marchant s.n. (UBC [UBCV221097, Suppl. Fig. 48, UBCV221096, Suppl. Fig. 49]); Hythe, Hants, male sterile, 50.8666°N, 01.3999°W uncertainty 7193 m, 10 Sep 1959, C.Marchant s.n. (UBC [UBCV221094, Suppl. Fig. 50]).

I am grateful to Ken Marr (V), Linda Jennings (UBC), Robert J. Soreng and Paul M. Peterson (US), Julie Shapiro (GH), Martin Xanthos (K), Luc Willemse (L), Bruno Wallnöfer (W), Pierre Moulet (AV), Mark Spencer and John Hunnex (BM), Albert Sanders and Sean Money (ChM) for help locating specimens and type specimens; Paul Sokoloff (CAN) for help scanning specimens; David Giblin (WTU) for specimen loans and permission to publish images from the University of Washington Herbarium, Burke Museum; Linda Jennings (UBC) for specimen loans and permission to publish images from the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum; Frank Lomer, Gary Williams, Rose Klinkenberg and Rob Knight for kindly sharing information on Spartina in British Columbia; and Paul Peterson for comments that improved the manuscript.

Holotype specimen of Spartina alterniflora (without collector, AV). Photo: Museum Requien. Specimen image reproduced with the permission of Museum Requien.

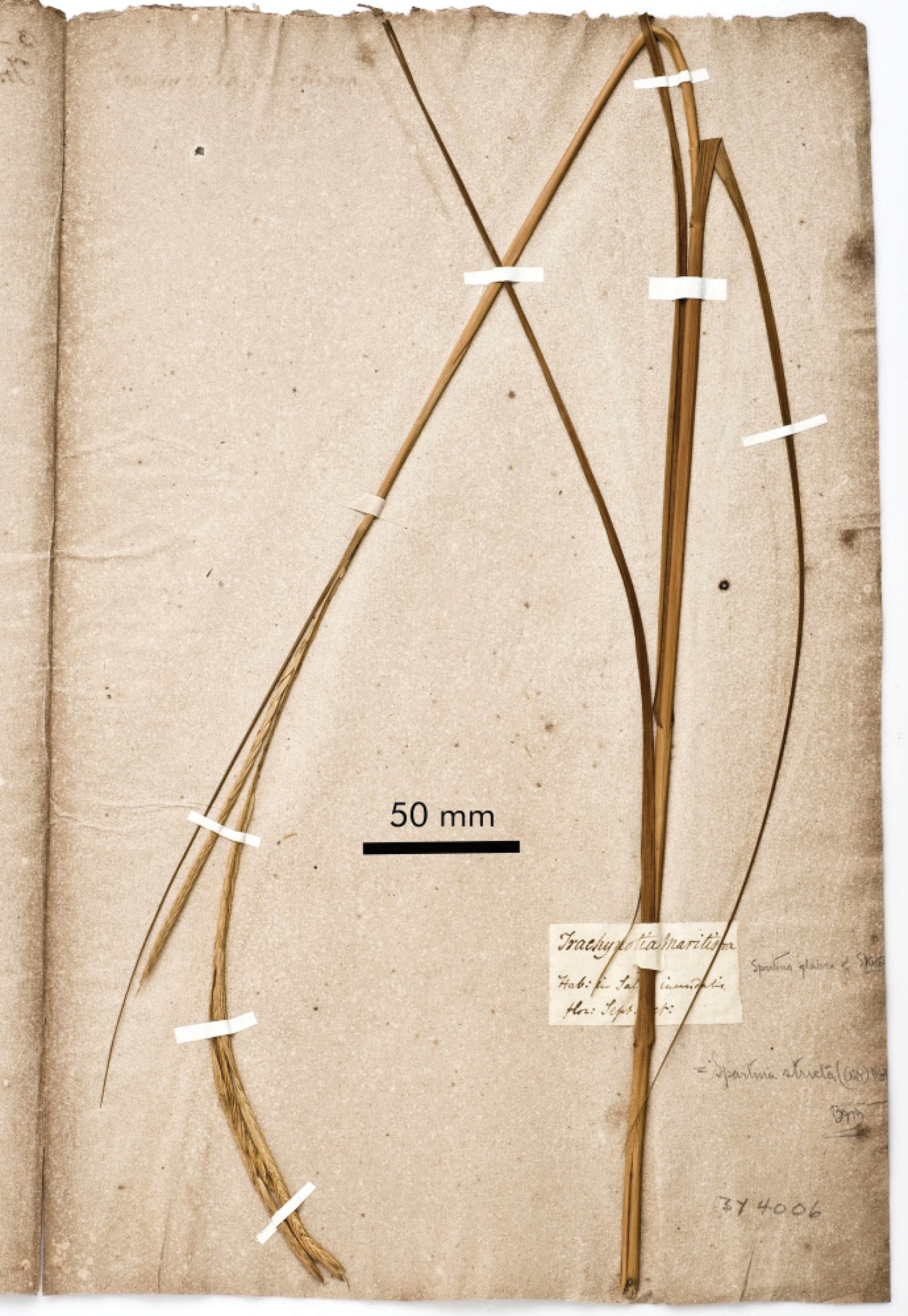

Holotype specimen of Spartina glabra (Elliott s.n., ChMBY4006). Photo: Sean Money, Charleston Museum.

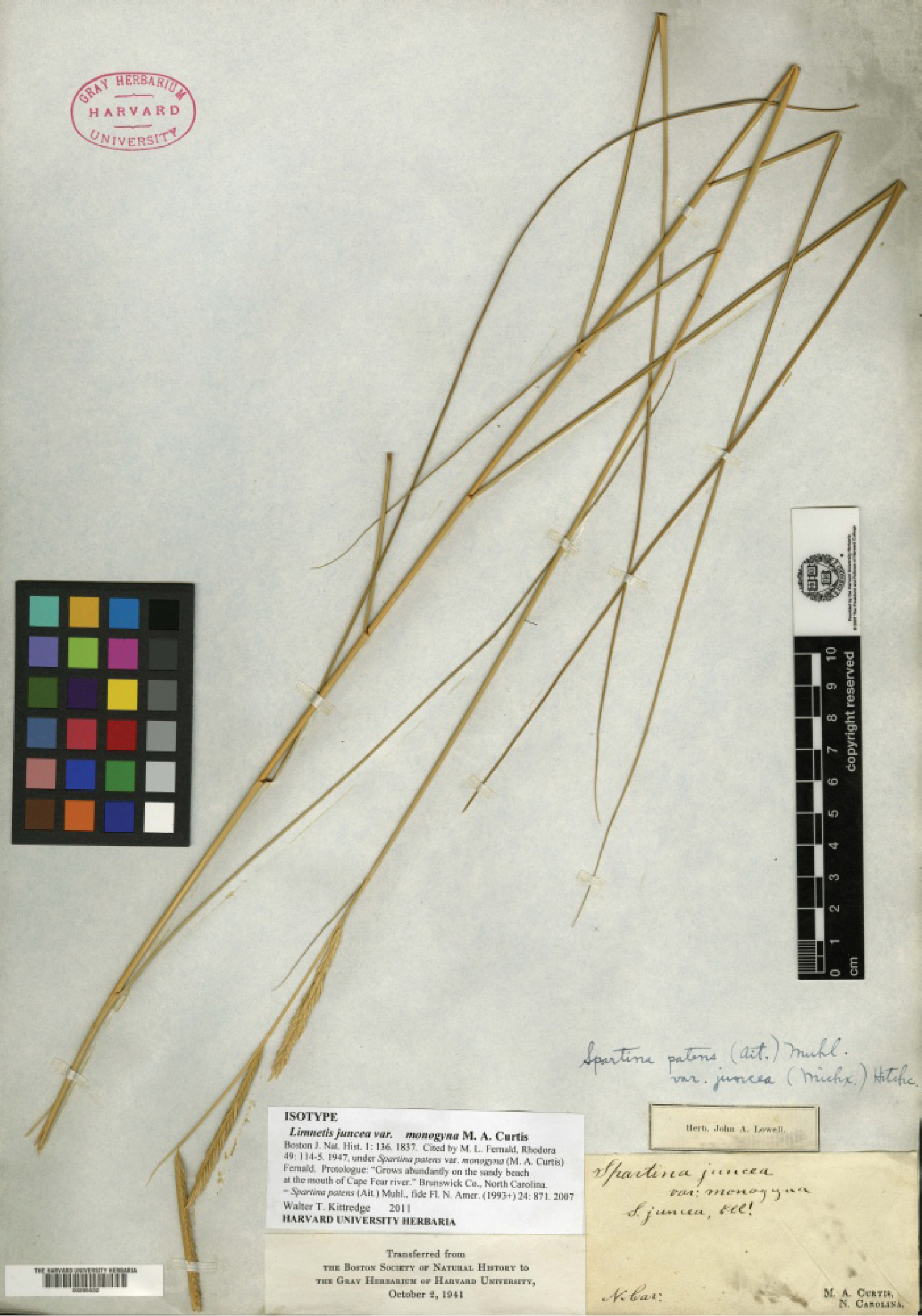

Holotype specimen of Limnetis juncea var. monogyna (Curtis s.n., GH [GH00295532]). Photo: Gray Herbarium of Harvard University Herbarium.

Supplementary figures

Exemplar Spartina herbarium specimens. (doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.10.2734.app) File format: JPG/ZIP.

Explanation note: Photographs of herbarium specimens of Spartina alterniflora, Spartina anglica, Spartina densiflora, Spartina gracilis, Spartina patens, Spartina pectinata, and Spartina ×townsendii. These are a subset of the specimens examined in the current study, as cited in the main text.

Supplementary figure 1. Spartina alterniflora, Maxwell 1575 (WTU342828). Image published with the permission of University of Washington Herbarium, Burke Museum.

Supplementary figure 2. Spartina alterniflora, Lebovitz s.n. (WTU344373). Image published with the permission of University of Washington Herbarium, Burke Museum.

Supplementary figure 3. Spartina alterniflora, Zika 18935 (WTU371783). Image published with the permission of University of Washington Herbarium, Burke Museum.

Supplementary figure 4. Spartina anglica, Williams 2004-3 (UBCV220132). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 5. Spartina anglica, Williams 2004-2 (CAN592131).

Supplementary figure 7. Spartina anglica, Walker 382 (WTU373426). Image published with the permission of University of Washington Herbarium, Burke Museum.

Supplementary figure 8. Spartina anglica, Zika 17595 (WTU365225). Image published with the permission of University of Washington Herbarium, Burke Museum.

Supplementary figure 9. Spartina anglica, R.E. Frenkel 3045 (UBCV196071). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 10. Spartina anglica, Frenkel 3045 (WTU305390). Image published with the permission of University of Washington Herbarium, Burke Museum.

Supplementary figure 11. Spartina anglica, Weinmann 233 (WTU370619). Image published with the permission of University of Washington Herbarium, Burke Museum.

Supplementary figure 12. Spartina anglica, Giblin 244 (WTU364297). Image published with the permission of University of Washington Herbarium, Burke Museum.

Supplementary figure 13. Spartina anglica, Giblin 270 (WTU364317). Image published with the permission of University of Washington Herbarium, Burke Museum.

Supplementary figure 14. Spartina anglica, Zika 19170 (WTU355108). Image published with the permission of University of Washington Herbarium, Burke Museum.

Supplementary figure 15. Spartina anglica, Jørgensen & Svendsen s.n. (CAN358861).

Supplementary figure 16. Spartina anglica, Matthews s.n. (CAN448159).

Supplementary figure 17. Spartina anglica, Riddelsjell s.n. (CAN467908).

Supplementary figure 18. Spartina anglica, Thompson s.n. (UBCV1679). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 19. Spartina anglica, Taylor 5378 (UBCV20934). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 20. Spartina anglica, Taylor 5379 (UBCV69243). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 21. Spartina anglica, Melvill 1841 (UBCV1678). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 22. Spartina anglica, Oliver s.n. (CAN421006).

Supplementary figure 23. Spartina densiflora, Lomer 7377 (CAN).

Supplementary figure 24. Spartina densiflora, Heimer 01-01 (UBCV224048). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 25. Spartina densiflora, Heimer 01-01 (WTU349303). Image published with the permission of University of Washington Herbarium, Burke Museum.

Supplementary figure 26. Spartina gracilis, Macoun 77227 (CAN33944).

Supplementary figure 27. Spartina gracilis, Macoun s.n. (CAN33943).

Supplementary figure 28. Spartina gracilis, Kujala & Cajander s.n. (CAN394014).

Supplementary figure 29. Spartina patens, Lomer 87-001 (UBCV194265). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 30. Spartina patens, Zika 20160 (WTU359724). Image published with the permission of University of Washington Herbarium, Burke Museum.

Supplementary figure 31. Spartina patens, Frenkel 3060 (UBCV196070). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 32. Spartina patens, Frenkel s.n. (WTU286900). Image published with the permission of University of Washington Herbarium, Burke Museum.

Supplementary figure 33. Spartina pectinata, Lomer 6805 (UBCV227406). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 34. Spartina ×townsendii, Saarela & Percy 791 (UBCV228476). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 35. Spartina ×townsendii, Austenson s.n. (WTU229915). Image published with the permission of University of Washington Herbarium, Burke Museum.

Supplementary figure 36. Spartina ×townsendii, Marshall s.n. (CAN585633).

Supplementary figure 37. Spartina ×townsendii, Groves & Groves 4596 (CAN251679).

Supplementary figure 38. Spartina ×townsendii, Halliday 457/77 (CAN522593).

Supplementary figure 39. Spartina ×townsendii, Halliday 100/66 (CAN301583).

Supplementary figure 40. Spartina ×townsendii, Groves s.n. (CAN421009).

Supplementary figure 41. Spartina ×townsendii, Marchant s.n. (UBCV221074). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 42. Spartina ×townsendii, Marchant s.n. (UBCV221101). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 43. Spartina ×townsendii, Marchant s.n. (UBCV221098). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 44. Spartina ×townsendii, Marchant s.n. (UBCV221100). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 45. Spartina ×townsendii, Marchant s.n. (UBCV221095) Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 46. Spartina ×townsendii, Marchant s.n. (UBCV221093). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 47. Spartina ×townsendii, Marchant s.n. (UBCV221099). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 48. Spartina ×townsendii, Marchant s.n. (UBCV221097). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 49. Spartina ×townsendii, Marchant s.n. (UBCV221096). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Supplementary figure 50. Spartina ×townsendii, Marchant s.n. (UBCV221094). Image published with the permission of the University of British Columbia Herbarium, Beaty Biodiversity Museum.